Learning language involves much more than memorizing the ABCs. How do babies and toddlers acquire language and how can parents and caregivers foster its optimal development? On this episode of Screen Deep, host Kris Perry is joined by renowned child development researcher Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, PhD, to discuss children’s language development, learning, and play in the digital age. Dr. Hirsh-Pasek emphasizes the importance of social interaction in the development of language, and discusses how digital media typically lacks this critical aspect and may even interrupt the language-learning process. She also describes the key pillars of learning gleaned from decades of research and the effectiveness of guided play in achieving learning outcomes. Dr. Hirsh-Pasek provides listeners with key insights on choosing effective educational apps, as well as maximizing learning opportunities, and critical skills children must develop for the digital future.

Listen on Platforms

About Kathy Hirsh-Pasek

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, PhD, is a Professor of Psychology at Temple University, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and a Visiting Professor at Oxford University. She served as President of the International Congress for Infant Studies, was on the Governing Board of the Society for Research in Child Development, and is on the board of Zero to Three. Hirsh-Pasek is the author of 250+ publications and 17 books, including Einstein Never Used Flashcards (2003), Becoming Brilliant (2016), and Making Schools Work (2022). She has won awards from every psychological and educational society for her translational work designed to bridge basic science and educational impact. She also was honored with the Simms Mann Award and the Association of Children’s Museum Great Friend to Kids Award. She is a founding member of the Latin American School for Educational and Cognitive Neuroscience and is the co-founder of the global Learning Science Exchange Fellowship (LSX). In 2021 she was elected as a member of the National Academy of Education. Her Playful Learning Landscapes initiative re-imagines cities and public squares as places with science -infused designs that enhance academic and social opportunities. Her recent initiative, Active Playful Learning, brings together leading scientists and educators to re-imagine early education in the United States. Hirsh-Pasek frequently comments for the press (e.g. NPR, NYT) and blogs for the Brookings Institution.

In this episode, you’ll learn:

- How babies and young children develop language.

- Why the quality and quantity of caregiver interactions shape a child’s early language journey.

- How media use – by children and parents alike – can affect learning and development.

- Why play is an important aspect of successful learning – and how best to incorporate it.

- How to evaluate and choose learning apps that benefit young children.

- The “6 C’s” of critical learning children need to thrive in the digital age.

Studies and resources mentioned in this episode, in order mentioned:

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Eyer, D. E. (2003). Einstein never used flash cards: how our children really learn–and why they need to play more and memorize less. Emmaus, Pa., Rodale.

Golinkoff, R. & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2016). Becoming Brilliant: What Science tells us about raising successful children. APA Press.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M., Nesbitt, K., Lautenbach, C., Blinkoff, E., & Fifer, G. (2022). Making schools work: Bringing the science of learning to joyful classroom practice. Teachers’ College Press.

Hart, B., & Risley, T.R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes.

Masek, L. R., Paterson, S. J., Golinkoff, R. M., Bakeman, R., Adamson, L. B., Owen, M. T., Pace, A., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2021). Beyond talk: Contributions of quantity and quality of communication to language success across socioeconomic strata. Infancy, 26(1), 123–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12378

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., Owen, M. T., Golinkoff , R. M., Pace, A., Yust, P. K. S., & Suma, K. (2015). The Contribution of Early Communication Quality to Low-Income Children’s Language Success. Psychological Science, 26(7), 1071-1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615581493

Ramirez, A. G., Zosh, J. M., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2024). Exploring dialogic interactions in grandparent-grandchild conversations over video chat in the United States. Journal of Children and Media, 18(4), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2024.2384977

Gaudreau, C., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2022). What’s in a distraction? The effect of parental cell phone use on parents’ and children’s question-asking. Developmental Psychology, 58(1), 55.

Reed, J., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2017). Learning on hold: Cell phones sidetrack parent-child interactions. Developmental Psychology, 53(8), 1428.

Watson, J.M., Strayer, D.L. (2010). Supertaskers: Profiles in extraordinary multitasking ability. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 17, 479–485. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.17.4.479

Pesch, A., Todaro, R., Piper, D., Evans, N. S., Pasek, J., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2024). A bird’s-eye view of phubbing: How adult observations of phone use impact judgments, epistemic trust, and interpersonal trust. Mobile Media & Communication, 12(3), 536-563. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579241246726

Roseberry, S., Hirsh‐Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2014). Skype me! Socially contingent interactions help toddlers learn language. Child development, 85(3), 956-970.

Zosh, J. M., Fisher, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2013) The Ultimate Block Party: Bridging the science of learning and the importance of play. In M. Honey & D. Kantner (Eds.), Design, make, play: Growing the next generation of STEM innovators. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis, 95-118

Hassinger-Das, B., Palti, I., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Urban Thinkscape: Infusing Public Spaces with STEM Conversation and Interaction Opportunities. Journal of Cognition and Development, 21(1), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2019.1673753

Nesbitt, K. T., Blinkoff, E., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2023). Making schools work: An equation for active playful learning. Theory Into Practice, 62(2), 141-154.

Meyer, M., Zosh, J. M., McLaren, C., Robb, M., McCaffery, H., Golinkoff, R. M., … Radesky, J. (2021). How educational are “educational” apps for young children? App store content analysis using the Four Pillars of Learning framework. Journal of Children and Media, 15(4), 526–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2021.1882516

Romeo, R. R., Segaran, J., Leonard, J. A., Robinson, S. T., West, M. R., Mackey, A. P., … & Gabrieli, J. D. (2018). Language exposure relates to structural neural connectivity in childhood. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(36), 7870-7877.

Masek, L. R., McMillan, B. T., Paterson, S. J., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2021). Where language meets attention: How contingent interactions promote learning. Developmental Review, 60, 100961.

[Kris Perry]: Hello and welcome to the Screen Deep podcast where we go on deep dives with experts in the field to decode young brains and behavior in a digital world. I’m Kris Perry, Executive Director of Children and Screens and the host of Screen Deep. Today I am thrilled to be joined by Dr. Kathy Hirsch-Pasek, a professor of psychology at Temple University and author of over 250 publications and 17 books, including the award-winning best-selling Einstein Never Used Flashcards, Becoming Brilliant, and her most recent, Making Schools Work. Among her many other credentials, Kathy is a child learning and language development expert beyond compare, and we have so much to learn from her today. Welcome, Kathy.

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: It’s so great to be here, Kris, thanks for having me.

[Kris Perry]: Kathy, we could probably talk for hours about only one area of your scholarship and expertise, but today I want to go big and focus on early childhood language development, learning, and play. So to start us off, can you give us the 20,000 foot answer to this question? How and when do babies acquire language?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Wow, that is – that’s a very big, big question. But you know, kids are kind of programmed to learn language in the same way spiders are programmed to spin webs. If they get the right stuff, out it comes. And what is the right stuff? The right stuff is having conversations. If you have conversations, believe it or not, even with a baby, all right, when you say something and the baby goes “caah”, at three months of age, and then you respond, and then they go, “eep”, that’s a conversation. And that conversation starts really, really early. And then those conversations build and build and build, and we extend what the child knows as they hear us speak, they click into certain things in language, they’re hearing patterns. I know you won’t believe this, but by nine months of age, they’re little statisticians, and little statisticians can already figure out the patterns that are in the language that they’re hearing. And in fact, they can even hear two languages and eventually they’re even going to sort out that the pattern of one language is a little bit different than the pattern of the other language. And so they’ll be beautiful bilinguals. And by, oh my gosh, by 24 months of age, by two years, those kids are already able to do things like code-switching. So, those conversations are kind of the basis. And what that tells us, which I find fascinating, is that language development is based in a social brain. It needs humans — back and forth conversations with humans. And what we have learned in the last eight years, 10 years, is that those conversations actually build brain structure and brain connectivity. As they’re building language, they’re building so much more. You’re helping your child with attention, you’re helping your child with memory. All these things come together. So that social brain is really key. The language comes in, the kids are primed to hear it, and eventually they start grabbing words at around, well sometimes even as early as 10 months of age. They certainly have receptive language before they blab it out to you. The average is that by 12 months of age— 12 months, just think about that — they’re hardly saying anything, maybe they have their first word, but they understand 50. Isn’t that incredible? And then life goes on and that 18, 19, 20, 21-month-old starts to grab onto language so quickly that the 21-month-old is learning up to nine new words a day. Now I want you to think about that. If you were taking a foreign language, and you could learn 63 new words a week, wouldn’t you be blown away? I mean, I’m blown away by this. By two years of age, this little thing is already putting words together. It’s already understanding the grammar of our language. Like, we don’t do well at that in eighth grade! But our kids are already using it when they are two. So, language takes off from there. Once they can put these words together into sentences, and they become somewhat demanding sometimes as they do that. “No” becomes a prominent word, they know they have the control of language. And of course, where’s the dictionary? It’s in your head. And by speaking with them, not at them, we’re giving them the large dictionary that we have in our vocabularies. And finally, I have to bring in the three-year-old. That wonderful three-year-old, knowing the command that they have. Here they are, I always talk about it as the terrible threes, not the terrible twos, because they know what they got. And the famous word that comes out then — “Why? Why? Why? Why?” They’re just trying to figure out what “why” means, but as you answer, you’re giving them such elaborate conversation, and that conversation is what helps build their world knowledge and later helps build their vocabulary, their language, and then leads us on to literacy. I think that’s the fastest I can do it.

[Kris Perry]: In terms of the essential conditions to babies acquiring language, many of which you’ve just laid out, including conversation, is it the amount of words babies hear, or how much time they spend babbling, or as you say, a social quality with their interactions and caregivers?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: I think, um, most of us have come to the conclusion that it’s quality over quantity. All right? Those conversations are really key. If I were listening, let’s say, to a string of words, it wouldn’t help me at all in memorizing those words. We all know that from when we took the SAT. Very few of us today know what the word ubiquitous means, and very few of us know what syzygy is. Okay, so we kind of lost that, and that’s okay, because that’s not the way we learn. Fun experiment: So many years ago, there was an experimenter who said, well, it would be interesting to look at these parents who are deaf and who have hearing children. And some of them trying to do the very best they could for their kids. What they did is they let the television be the guide because the television had language that was coming at them. And in many studies since then, what we’ve learned, is the blabbing that goes on in television, it doesn’t quite reach the ears, well, maybe reach the ears, but it doesn’t reach the mind of the language learning child. It’s the interactions that matter and the way we build on each other. That’s the magic sauce.

[Kris Perry]: Okay, in terms of the quantity versus quality dichotomy that you just laid out, it makes me think of the famous 30 million word gap study. Can you explain that for the listeners and whether or not that explains disparities in language development environment?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: The 30 million word gap came from a study that was run by Hart and Risley. And it’s probably the most controversial study that has ever been done in the field of language acquisition. What did they do? On the basis of 40 parents and kids–hear that number, four-zero– they divided parents into the more resourced, the kind of middle income, and the under-resourced families. And then they looked to see how many words were actually delivered in conversations to the children. And what they found is that the kids who were in the more resourced environments got tons more words than the kids who were in the under-resourced environments. Now, that’s controversial for many reasons. One, as I’ve already mentioned, quality seems to be even more important than quantity, though I should tell you that they’re highly correlated. That is, when you have more conversations that are of high quality, you’re probably getting more words. All right. But there are cultural differences in how people deliver language to young kids. In some cultures, you don’t talk a lot to a child. And in fact, many parents believe, falsely held, but they believe that young children aren’t paying attention to them anyway. What’s an 18-month-old know? What’s a six-month-old know? So there are lots of things that confound what’s going on in the Hart and Risley data. That said, there are a lot of differences in the environments. Sometimes you have a TV background noise all the time, which cuts out the ability to have those conversations, or at least is distracting. Sometimes, in fact 20 percent of the time, you have kids who have a lot of ear infections, and if you have those kids who have a lot of ear infections, they really don’t hear you as well. So, it’s harder to get the responses you want. Having said all that, still, when we have looked in study by study by study, what we do find is that there is a divide, such that children in more resourced environments, for whatever reasons, are getting a lot more language input and are getting a lot more conversations, and are getting a lot more world knowledge in those conversations. And that’s still something I think we have to reckon with. So, I don’t really believe in the first study of 40 kids, but as we’ve looked at it, even within group, a student of mine, Lillian Maseck, did a gorgeous study, and it was within the lower income families and those families who spoke more with, not at their children, had kids with better language skills.

[Kris Perry]: How should we be thinking about addressing disparities in home environments for language acquisition and development?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Well, I think for one, what you’re doing by having a podcast is really helpful. You know, one of the things we have to do is not have distractors. We have to look into the eyes of a child and we have to have those conversations. Just take a minute of time and look in the eye of your child and see what your child’s noticing and comment on it and have that conversation. Even if they can only coo, even if they can only “goo goo,” it’s okay. Still, let that conversation start to bud. And I think knowing that and knowing that it has something to do literally with brain development and brain connectivity is a good start, okay, that’s informing the public. Another is that there are many, many fabulous intervention programs that are working with families to help expose what can be done. And I think every parent, at least I’ve ever met, wants the best for their child. So learning some of these tricks makes a big difference. If you looked at all of these interventions that we’ve done, we’re all hitting back-and-forth conversation, rich with words. I don’t care if you were talking about the slugs that live under the rocks in your front yard, or how grass grows, or looking at the ants. If that kid’s interested in it, have a conversation about it. Now, there’s one more thing that means. It means you’ve to put your cell phone away. Because when it bleeps and it buzzes and it rings, your tendency is to take your eyes off of the child and onto the phone, even for that one second. But what we need are a little bit of free zones where we just listen to, talk with, and have engagement with our kids.

[Kris Perry]: I wanna flag a couple of other things that you’ve already mentioned that weigh heavily on my mind when I think about displacement or distraction in homes where young children are learning language. And you mentioned televisions and cell phones, for example, and how they interfere with conversation, and that conversation is directly tied to language development. So A plus B equals C or not. What does the research say about screen use and how that might relate to language development?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Well, you know, it’s all over the map, to be quite honest with you. But there are recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics. There are recommendations by the British Academy of Pediatrics. All over the world, we see the same things are being said by the experts. And that is: turn it off, especially if they’re under two. You know, you want to have FaceTime, FaceTime can function much like live, not entirely, but grandparents, be happy: the latest data, Roberta Golinkoff just published on this, and the data that we have had for years, and Pat Kuhl had for years, suggest that it’s a reasonable substitute and the child will actually know you when you go there, if you happen to be a remote grandparent who doesn’t live next door. So that’s a good one. But, more than FaceTime, I would say skip her. And that’s what all the recommendations are. Now having said that, I fully understand that parents need to take a shower, and they need to have their kid occupied while they’re cooking dinner. And as a mom of three kids, I get it. So yeah, do what you need to do, but recognize that it’s not a reliable babysitter. And especially at a time when there’s language learning, let me assure you, that the television does not know, nor does an app, know how to be adaptable. It may be interactive sometimes, but it is not adaptable in a conversation with a little person. And that adaptability is what matters.

[Kris Perry]: I’m thinking of some studies you were involved in that looked at parent or caregiver screen use and how that might relate to learning or communication development in children. And I’m thinking of a study from 2017 that had some interesting findings in terms of the effects of phone interruption to the learning process of toddlers, and a 2022 study that measured child question-asking when parents were on cellphones versus not. Can you talk about these and other insights about how the screen behaviors of caregivers are possibly impacting child learning and development?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: No, absolutely. I absolutely love the Just Read study, and Pat Kuhl had one that was very similar. But we were just doing a simple word-learning task, you know, and we asked the parent either to answer the phone when it rang or not answer the phone when it rang. Everything else was equal in the two conditions, okay. The number of words that were given, absolutely everything. And what happened is when the parent answered the phone– call that a conversation disruptor–when you had a conversation killer, the kids didn’t learn any of the words. And when you didn’t answer that phone, the kids learned all the words that we presented. Well, that’s curious, isn’t it? So, alright, what else happens when you’re on the phone? Well, when you’re on the phone, you know you’re kind of double timing it, really? And one of the things we’ve learned about humans, not my research, but just wonderful research that’s out there – this is going be such a shock to your listening public, I’m not sure I should say it – but human beings are not good multitaskers. Now, we all think that we are, but in reality, only 2% of us are what has been termed “supertaskers”. I think that study was by Steele who had done some of the work on multitasking while you’re driving. No, it doesn’t work, and that’s why there’s so many more accidents when you text and drive. Okay, so for that very same reason, you may think you’re still having a conversation with your kid when you’re engaged in something else, but you’re not, you know, and we can tell that from the data. You don’t ask the same kind of questions, the number of questions goes diving down, and note that questions are a great way to get conversations started. So drop the questions, you’re dropping the conversations. And that’s precisely what we found.

[Kris Perry]: I mean, don’t you feel it just as an adult if you’re with a friend having coffee or you’re in a meeting at the university, and somebody has one eye on their phone or they reach and grab their phone, that it immediately causes a reaction in us, that we’re less important, they’re not going to focus as well, that I might need to wait for them to finish. It’s true among adults, and we know just how vulnerable but also how magical those early years are and how critical every minute – I love that you said, try for just one minute, looking in the eyes of your young child and speaking to them in the most engaged, enthusiastic way possible, and just to see for yourself what response you get. I would love for people to do that, adults to do that. That would be fun.

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek] I have to tell you, I have to tell you about another study that we have that’s coming out. It’s on what’s called “phubbing”, this is called either “technoference” or “phubbing”. Okay. So we do this really cute thing where we film four people in a meeting, this is exactly like what you’re talking about, right? I had to know, I had to know. Okay. So there’s four people in a meeting and one of the people in the meeting picks up her phone and just takes a little peek at it, okay. I mean, she’s still in the meeting, she’s still having conversations, but she’s the peeker, she’s the cellphone user. Alright, so then what we do is we take all four people in this setting and we ask whether an adult who’s watching these videos, okay, all they did is watch the video. And remember, they’re at a meeting, we had the peeker, and the other three people weren’t peekers, okay? And we change the peeker in the videos, you know, so you can tell whether this is a real effect. And then we ask, “Would you trust this person?” Okay, we take a measure of trust and we say, and we have all four people there, would you trust this one, this one, this one, this one. Would you want this person to be your friend? This one, this one, this one, this one. Okay, so what do you think happens? The peeker dives on trust. The watcher doesn’t trust the peeker. Duh, okay? And, wouldn’t want to strike up a friendship with that person. So this is work that was done by Annelise Pesch that I think is absolutely brilliant. And wow, okay, if that’s happening with adults, what’s happening with kids? Well, we’re running the study right now. And another thing I really want to do that I think is another conversation killer is that we’re taking pictures of our kids all the time. So we might be having a perfectly good conversation with our kid and out comes the camera. Okay, now let’s just talk about what happens in that moment. Yes, you have recorded it along with everything else you’ve recorded. Yes, you may be able to put it on, Facebook to say that you actually were there. But really, you missed an opportunity. You may have the picture, but you missed an opportunity to talk with your kid while you were busy taking pictures. So I think we really have to look at our own behavior and to see what we, we as parents, are missing in the conversation.

[Kris Perry]: You mentioned the reality that sometimes a parent may turn to screen media when they need a minute to themselves, and I know the recommendations after two years old start to allow some media use, especially for education and learning. A study of yours from 2013 looked at vocabulary acquisition from passive video watching, interactive videocalling, and live instruction. Can you tell us what you found?

[Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Yeah. Absolutely. So there you go. You know, we try to make it as equal as possible, okay. So we had — either you were getting information from someone who was live on the other end, so think Zoom, okay, Zoom didn’t exist then, but this was pre-Zoom, but we did it. You know, FaceTime, Zoom. The second is on television, same stuff’s being discussed, but it’s like now on television, so it’s not linked, it’s not linked to what’s happening with the kid. And then we did live. Okay, so here is the million dollar question. Where did the kids learn the words best? Bum, bum, bum, bum, bum, bum, bum. Okay the answer is — they didn’t learn them from television, because when it’s not adaptable, when it’s not yoked in the conversation, it doesn’t work. Where did they learn it? They learned just about as well in a FaceTime Zoom conversation as they did live. That’s amazing. Now notice we were trying to control. So in the real world, live is absolutely better than anything else you can do, ‘cause you have all these nonverbal cues that go along with it as well. And seeing the whole body really does make a difference, orientation, et cetera. But I would say to you, anytime you can engage in a conversation, it’s a good thing. Now we all know what happened over COVID, right? And that is that the kids tanked in some of their vocab and reading and in math because it doesn’t work as well over a screen as it does live. And if we thought we were fooling ourselves before then, we need only look at the data post-COVID. So, I think what we’ve learned is being with real people, being engaged with real people – with kids, with teachers, with friends, with family, makes all the difference for how we learn.

[Kris Perry]: Absolutely. Beyond early language acquisition, I know you’re deeply involved in studying children learning as it relates to play and playful learning. What conditions are necessary for children learning?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Well, actually, we’ve come up with kind of a little – quick, you’d call it a tweet, I guess, that when it’s active and engaging, when something’s meaningful, when it’s socially interactive, when it’s iterative and it is changing a bit and it’s adaptable, and when it’s joyful, you learn best. Alright, so let’s play with that, okay? Um, when we are playing, when we are engaged in play, we are all there, we are minds on, right? We’re like, in the zone. And so are our kids. Sometimes our little people, you know, our three, four, fives, my gosh, they could play ball with you for way longer than you want to play ball. Back and forth. But, that’s kind of a conversation, right? A well-timed conversation, beautifully executed. But your mind’s on. And then are you engaged? You bet you’re engaged because it’s harder to distract a kid from play, right, than it is to distract a kid who’s bored. Then we can think about meaningful. It’s meaningful to them when they’re playing and it’s meaningful to us too when we’re playing. Socially engaged, we’ve talked about that before. Real people, real timing. Look at our conversation right now. If we were to diagnose this, by the millisecond Kris, by the millisecond, we respond to each other, visually and in sound, and in meaning. All these things are aligned. Our emotions are aligned, it’s one beautiful thing that evolution gave us. Okay? Meaningfulness, socially interactive. And we’ve changed the conversation in the course of this podcast. So it’s iterative. We’re learning more each time you ask a different question. And finally, I’m having fun. I hope you are.

[Kris Perry]: I mean, of course I am. I am already dreading the fact that this will come to a close, this conversation. So let’s talk a little bit about other places kids go. So should schools and communities be incorporating more play into learning environments? Because I know you have been involved in many really exciting community projects and initiatives that are incorporating more of these elements of play and would love to hear more about them.

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Sure, as one of our–I think one of the most exciting projects I’ve ever worked on. It’s called, “Playful Learning Landscapes,” and it was an idea that came to me, like, on a Sunday afternoon when I was just thinking like, look at all the time we wait. Like we have a lot of places where we wait, you know? And we’re with our kids. Now think of those places right now. Those of you who are out there, think what happens if you go on a bus. You go to a train station. What do you do? You’re sitting right next to your kid and you pull out your phone. Right? You’re at a library. You pull out your phone. So how do we engage families more in these places where you wait? So it was a pretty crazy idea. But it started with this thing that I call “The Ultimate Block Party.” And the Ultimate Block Party was our way of putting some of the science of learning, what I’m talking about right now, into the streets to see if people responded to it. I decided we could take over Central Park and put 26 science-inspired activities all through the park to watch parents and kids engage, and see what happened. And everyone was so excited. Having conversations with kids, having conversations with other kids who weren’t their own. And I realized what we had created here was a kind of Italian piazza, a new public square. And then I had this idea that maybe we could extend the public square to everywhere. And I thought, “My gosh, we could build what we learned in the ultimate block party into bus stops.” How cool it would be if a bus stop wasn’t just a place that you sat and waited for the bus, but it had cool things to do, like puzzles you could play. So we ran the study, and we saw parents didn’t just sit there on their phone anymore at the bus stops. You could build the cognitive opportunities right into the bus stop. So once we knew that, man, we went insane. We went to libraries, supermarkets, where we either had signs up or signs down conditions. We’ve done this stuff all over the world now. It’s unbelievable. And so that’s “Playful Learning Landscapes” and I encourage the listeners to just go to playfullearninglandscapes.com. So if it works so well, out of school, why is the first thing that comes to mind– Well, let me ask the question. What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of school?

[Kris Perry]: That you’re in a structured setting where you can’t be as creative and you can’t alter the environment. You’re placed in a very fixed environment.

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Yeah, and the number one answer most people give from that fixed environment is?

[Kris Perry]: Boredom.

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Boredom. You got it. I mean, you got it. That is the 80% answer. So it doesn’t have to be that way, and teachers don’t want it to be that way. They’ve been handcuffed. Teachers know how to engage kids in an active and engaging and meaningful, socially-interactive way. I love teachers. They want to be there. So how do we take the handcuffs off? So, in a project that we’re currently doing called, “Active Playful Learning”. And it’s with honestly the most exquisitely good scientists who have worked in early education in the United States. You have to look this up at activeplayfullearning.com and you’ll see who’s involved. We’re in four states right now, in Virginia, in California, Illinois, and why am I missing one? Texas. And we are literally taking coaches. We are going into classrooms. We’re working with teachers to create what we call active, playful learning. And we’re hoping, we’re hoping that as those classrooms become more active, engaged, meaningful, socially interactive, iterative, and joyful, that the teachers will be happier, absenteeism will be lower, and they’ll actually learn at least as well, if not better, on their standardized tests.

[Kris Perry]: Yeah. Thank you so much for sharing all those great examples of learning environments in the real world. And now I want to think about screen environments again and the difference between play and learning where really they get sort of blurred. And you know, in this age of gamification and educational apps and all of this content that’s really being delivered to parents online, how can parents know what is peer play or entertainment or what is an actually helpful educational tool that incorporates play?

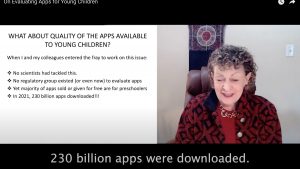

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Wow, that is the million dollar question. So we’ve come up with a series of pillars. I guess you can already guess what they are. Come back to my tweet, you know. If it’s active and engaging, meaningful, socially interactive, iterative and joyful, that’s the “how” of learning. That’s the “how” of learning. And you can apply it to any content. You can apply it to math. You can apply it to vocab. You can apply it to learning how to do narrative and language and reading. If you have those qualities, then you end up with a better app. And as part of meaning, I would also say it should be culturally variable and meaningful to the people who are using it. So we’ve come up in our lab with what we call, “The Three-Part Equation.” And the Three-Part Equation is first, what can we learn that’s meaningful from the cultures that we’re in? So that we don’t just deliver an app, but we deliver something that’s authentic and can help kids learn through that authenticity. And how do we find that out? By people. We have interactions and focus groups with people. Then we move to part two. Part two is the “how do kids learn?” Build it in. Active, engaged, meaningful, socially interactive, iterative – but, with a real learning goal. And that takes play to what we call, “guided play”. It can be designed by designers, but they must know their stuff and not just create a goal and “Now we’ll do math.” Well, what do we know about math? We know a lot about how kids develop math. Speak to the experts, partner with them. If we have developmentalists with developers, we’re going to have stronger apps. And there’s evidence from that, from Oxford University, from Sandra Mather’s work. When we have had apps that were done with developmentalists and people who know the science of learning, those apps have sticking power and the kids learn more from them. That’s part two of the equation. Number three is that we need to get out of the mindset that it’s just about doing better in reading and math. To learn means to know how to collaborate with other human beings, navigate the social setting. To learn means knowing how to communicate with others in language that they understand and to have that conversation. To learn means to know your content, but also know how to learn to learn. It means to have critical thinking, creative innovation, and the confidence to try something new. And we can build those features in. And if I may brag about one app that I’m very fond of, it’s Rangeet, which is out of India and is now reaching millions and millions of teachers and millions of students, and they have something that works with climate and it’s also working using the “Six C’s” which I just gave you: collaboration, communication, content, critical thinking, creative innovation, and confidence. And if you build that in you can make something so special. So how do I know a good app from a bad app? Which was your original question? Did they follow the three-part equation? Do they have something that’s active? That’s engaging, that’s meaningful, socially interactive, is something iterative? That each time I go back to it, it’s not the same thing. I’m not just getting a grade. I’m not just getting hand clapping when I get the right answer. It takes me to a new place, and it’s fun. And those can be developed. People at Carnegie Mellon are working on such apps right now. They have a great team there. So, I think we can do it, and I think that taking on the challenge, so app developers out there, hear me. We know how to do this and if we don’t and we’ve run the test. We did the 100 most downloaded apps. Meredith Meyer and it was Jenny Radesky’s lab that did this. The 100 most downloaded apps. How many of them came out as truly educational apps? Really good apps? Three.

[Kris Perry]: That’s sort of shocking and it actually–my next question was going to be, “Who else is doing playful learning well in media for children that you’ve seen?” But it sounds like from Radesky’s work and others, it’s a very small number at this point, but you’ve done a really nice job of helping us all understand what those critical components are, the essential ingredients to not only real-life quality interaction, but online, digital-life interaction. You also mentioned the six C’s just now. And I–I know you introduced this concept in your book, Becoming Brilliant, as the essential skills children should learn or develop for success in the information age. Can you repeat those six C’s again and share how families and communities can help children develop these skills and when they should start?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Yeah, well, you know, we should start like now. You know, when they’re born, because kids have to learn collaboration from a very early age. And that’s why I say, you can never take the human part “out”. Even when we’re talking about, you know, screen time, humans are an essential part when a child is young. And there are many ways to think about that. It can be co-viewing, right? It can be co-doing. And we need, I think, to do more of that. We’re not really good at that. And in fact, I just read a paper this week that it’s something like, only 30% of parents are really, you know, listening to the wise words of the American Academy of Pediatrics. So, collaboration, start immediately. All right, next go to communication. You know, talking to even the baby matters. Babies are hearing us. And even if they can’t have the conversation back, know that they’re listening. They’re looking for patterns from a very early age. Move to content. We don’t need to teach the ABCs and the one, two, threes to kids when they’re too young. It’s meaningless. I know it’s on all this stuff out there. But honestly, I’d say, “skip it”. Help your kid not become a widget. Help your kid become a great human being. And you’re going to be doing something terrific. We don’t want widgets, we need humans. And then as they get older, when they’re four and five, you know, it’s fine. Maybe even, you know, late threes. It’s fine to introduce them to some of that, but make sure it’s meaningful, not just memorizing it. If you have to know a letter to unlock some clue, okay. But if you’re just memorizing a dumb letter, who cares, okay? Then, critical thinking. Because everybody says, “My kids don’t have critical thinking.” I disagree completely. Alright? And this is a true story. My granddaughter, Elena, had a crisis when she was about 3 and a half. And the crisis was that the ball she was playing with rolled under the couch. She called me on FaceTime to tell me that she was beside herself, because she couldn’t figure out what to do. Crying, she said that her projected arm did not reach far enough to get the ball out from under the couch. And I said to her, “Well, what do think we can do?” “I don’t know.” I said, “Well, is there any way to extend your projected arm?” So all of a sudden she said, “Yes, I’m going to go get a spatula.” Well, she got the spatula and her projected arm and the spatula were still not long enough to solve the problem. And eventually she moved on to a broom and that did work. That’s critical thinking. Yes, little kids are critical thinkers, all the time. And they are creators. Oh my gosh, are they creators? If we don’t kill it, they will be creators their whole life. And finally, confidence. It’s okay for a kid to fail. And our best thing we can do is say, “Yeah, you know, I got that wrong too. Let’s work on it a little harder. Stick to it. Make the tallest tower.” And if we do that, we’re setting them up for a lifelong success where they won’t just be worker bees. Now, worker bees? Worker bees aren’t going to have a job anymore. Because honestly, AI is a pretty good worker bee. It’s pretty good at summing up what’s out there in all the world’s knowledge since the beginning of time. But AI is not so good at being a real creator. It’s not so good at being divergent, you know? And I think we want to teach our kids all the skills they need to survive in an AI world so they can outsmart the robots.

[Kris Perry]: Are some communities doing it better, or more than others, in terms of helping children develop these 6C skills?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: I would say some, but not a lot. You know, you do see a lot of this in some of the private schools. And sadly, we’re not seeing it as much in the non-private environments. And you shouldn’t have to pay money for this. These are simple, you know? A ball can be made out of taking aluminum foil and smooshing it together. That’s a ball and I can play catch with it. It doesn’t cost a lot of money to do these skills. In fact, it doesn’t cost any. You can use kitchen utensils for most of them. But I think, it’s not being done well. And I think there is a movement right now in the United States to create more of this through what they’re calling, “competency-based education”. And I think for all of us, the question we need to ask ourselves is, “What do we really want for our children?” You know, “What’s the goal? What do we want them to graduate, you know, elementary school with or high school with? Is it just a good test score? Or is it that you want happy, healthy, thinking children who are socially-competent, creative innovators who are good citizens?” And you can choose amongst them. But for my buck, it’s about creating the latter.

[Kris Perry]: I don’t know if it was you, Kathy, or somebody else that we’ve talked to over the years who made the comment that the job that children will have when they’re adults, doesn’t even exist yet. That the kids in kindergarten don’t know what job they’re going to have. So, all of these great points you’re making about memorization and rote learning as compared to competency-based learning, social skills, ability to collaborate, being divergent, are all totally different skills. And I’m not sure we need to pit them against each other, but I think we don’t want to be lopsided when we’re thinking about someone’s overall development. And every one of those building blocks starts from the moment they’re born, maybe before, and all the way through their entire education and career. So it’s been really great to hear you talk about this so explicitly, because we don’t get to talk about how important all of those skills are. Now, what led you to devote so much of your career to early childhood learning and play and how do you incorporate play into your own life?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: That is such such a great question. I have been very lucky in my life to always work hard to try to maintain what a four-year-old sees in the world. And you know what? It’s a pretty beautiful world out there. The leaves on the trees, the variation in the leaves, the way the wind blows, the way the ants move. Just like everything is an adventure. And if you can hold onto that without the adultification, which we tend to do, then I think we see the richness in what our kids see more. And so for me, life truly is an adventure, and I try to hold on to that even when things don’t look so good. What’s the next adventure going to be? How can I see it differently? How can I appreciate what’s before me? And try to hold on to it because that richness, what our kids can teach us, is actually what’s going to help us be better leaders in this world to come. So we’re important, you know, because we have to give those adventures to our kids and have conversations about those adventures. But we have to live through their adventures too. And I guess that’s what really hooked me into caring so much about kids, because I think the golden, the golden, you know, jewelry that they give us every day–if we just appreciate that it’s there, and I know we get bothered by it sometimes. But hold onto it, even if it’s just once a day. I hate slugs, but I learned to look for them, because my kids were into it, you know?

[Kris Perry]: Your enthusiasm is contagious. Of all the work that you’ve done, what has been particularly surprising of all of the findings that come to mind and something, say, you weren’t expecting to find when you started out?

[Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek]: Wow there’s so much, I mean, the question is just where to start with that. The first thing I’d have to say is I was surprised that the quality of the interaction mattered more than the quantity of what went in. I was deeply surprised by what I think is one of the most magnificent findings by Rachel Romeo and her team, that it was building brain structure and connectivity. I was blown away by that. That these simple conversations are building the brain. And if I were to take a guess, I have another paper out with Kathy Thomas-Lamanda on this and Lillian Masek again being the first author, that it looks like it may be building attention too and executive function too. Like what if these early interactions are setting the stage for the whole cognitive structure of the way we think? I mean, that’s mind blowing. And yet we are social creatures who are endowed with a socially-gated brain, you know? And I’m amazed by that. The second was that I fully expected that play was going to be the key to learning. We’ve now done a number of studies where we have pitted free play, guided play, and direct instruction. And when we look at the three, free play is really active, engaged, meaningful, socially interactive, you know–joyful and iterative, but it doesn’t have a learning goal. So there’s too many other things the kid can be doing if indeed, if indeed your goal is to have the kids get some math out of it or to get some literacy out of it. It doesn’t work. You know, full stop. It just doesn’t work. Now, it’s great stuff to do. I love free play. Free play is wonderful for social engagement, for learning how to navigate what goes on in a playground. There’s nothing like free play. But if you have a learning goal, turns out it doesn’t work. And turns out that it’s, even direct instruction doesn’t work as well as guided play. Isn’t that amazing? And what is guided play? It’s stuffing that learning goal, as I told you we are doing in playful learning landscapes, putting the cognitive science, legitimate, cognitive science into the play creates a strong learning goal along with active, engaged, meaningful, socially interactive, iterative, and joyful. And when you do that, you have the magic sauce for how to help kids learn. Finally, let me say, “What is learning?” Learning isn’t just holding on to it, but it’s making it sticky over time and transferable to a new situation. If you only learned something for the test, then if the test is given a week later, you’re going to fail. But if you learn something deeply, so that you can then transfer it to new instances and new models and new problems, then you have a winner. So sticky and transferability, guided play. That was a surprise.

[Kris Perry]: I could talk to you forever about all of these amazing discoveries that you and your colleagues have made about language acquisition, play, children, their online lives, their real lives. You’ve done a remarkable job with us today. Thank you so much, Kathy. I appreciate you so much for taking the time to talk to us today about these foundational and fascinating processes in child development and learning. I am inspired by your work and how you are moving the needle on our understanding of what we can do to help children learn and thrive today. Thank you too to our listeners for tuning in. For a transcript of this episode, visit childrenscreens.org, where you’ll also find a wealth of resources on parenting, child development, and healthy digital media use. Until next time, keep exploring and learning with us.