Children and Screens held its #AskTheExperts webinar “Blood, Sweat, and Fears: Understanding the Psychological Effects of Graphic and Violent Media” on Wednesday, January 27th, 2021 at 12:00pm EST via Zoom. Moderator Dimitri A. Christakis, Director of the Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, led a dynamic discussion on the short and long-term psychological, social and behavioral impacts of violent media on children and adolescents, and the challenges parents and policymakers face in navigating and regulating such content online.

Through a thoughtful conversation and interactive question and answer session, our esteemed panel of multidisciplinary experts discussed the characteristics of media violence that are most detrimental for children’s well being, identified the influence of social media on gang behavior and real-life violence, and provided actionable insights for parents to counteract and mitigate the overall effects of media violence on their children’s mental and emotional well-being.

Speakers

-

Dimitri Christakis, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief; Director; Attending Pediatrician; Professor of PediatricsModerator

-

Brad J. Bushman, PhD

Professor

-

James Densley, PhD

Professor of Criminal Justice

-

Christopher Bartel, PhD

Professor of Philosophy

-

Douglas A. Gentile, PhD

Professor of Developmental Psychology; Editor; Co-Author

-

Desmond U. Patton, MSW, PhD

Associate Professor of Social Work; Associate Dean; Founding Director

04:30 Kicking things off with research video footage from Bandura’s classic Bobo Doll experiments and his own work studying gamers’ prosociality using an ordinary cup of pens, Dr. Douglas Gentile, a Developmental Psychology professor at Iowa State University, illustrates that children learn from observed aggressive behaviors. He notes that although viewing violent media will not result in fatal violent behaviors from children, when young people practice viewing or playing aggressive acts with high frequency, their worldview shifts from positive to hostile. As a result of a media diet with high amounts of violence, children are more likely to become involved in aggressive encounters and are less likely to be prosocial.

19:21 After sharing shocking statistics about gun ownership and young people’s exposure to firearms in the United States, Dr. Brad Bushman, professor at the School of Communication at The Ohio State University and Margaret Hall and Robert Randal Rinehart Chair of Mass Communication, presents two studies (one with movies and one with video games) which reveal that children who view media characters using guns are more likely to use actual guns (e.g., hold the gun longer, pull the trigger more times). Dr. Bushman encourages parents to protect children by keeping firearms locked up and out of sight and to educate children about media images and gun usage.

30:00 Dr. Christopher Bartel, Professor of Philosophy at Appalachian State University, speaks about the moral impacts of long-term violent video gameplay. He explains that morality is not something people are born with, but instead something we learn through practicing behaviors and habits. Dr. Bartel emphasizes that although our actions in violent video games are not real, the judgments we make to enact these behaviors are real. Video games can act as moral practice spaces, where players practice making both positive and negative moral judgments, and so practicing positive moral decision making is more beneficial than practicing making aggressive or violent decisions.

40:45 To explore an understudied element of media violence, Dr. Desmond Upton Patton, social worker and Associate Professor at the Columbia School of Social Work and Department of Sociology examines how social media, artificial intelligence, and community-based violence online relate to off-line violence among adolescents and notes that while in-person violence has decreased recently, online violence is on the rise. Dr. Patton examines the concept of “internet banging” and issues of well-being, grief and mental health by analyzing, with youth, the Twitter accounts of young people who experience community-based violence. Although it is hard for parents to know or understand what children are posting online, Dr. Patton urges parents to engage in open dialogue with their children about their online lives.

54:18 Dr. James Densley, Professor and Chair of Criminal Justice at Metropolitan State University in Minnesota, explains the role of social media, live streaming, and online incentives in the psychological grooming of future offenders, from school shooters to violent extremists. Dr. Densley implores parents and educators to teach and practice media literacy in order to combat online hate and participation in group violence.

1:04:00 The panel concludes with a conversation, answering questions from the audience, including how K-12 schools can educate their students about some of the risks of social media, video game recommendations that do not contain violence, how parents should handle violence in the news such as the recent U.S. Capitol invasion, and how violent media is only one risk factor for aggressive behavior in children and teens.

Pamela Hurst-Della Pietra: Welcome to our first Ask the Experts virtual workshop of 2021, and our 25th webinar since covid began. I am Doctor Pamela Hurst-Della Pietra, president and founder of Children and Screens Institute of Digital Media and Child Development, and host of this popular series. During today’s webinar about media violence, we will discuss how on screen violence and aggression impact children and adolescents. We’ll explore all of the nuances involved in the equation. Some of the images and conversation will be inappropriate for young eyes and ears, so please view this webinar in a separate space from your children. I would like to address upfront that our panel is full of men, which was not for lack of inviting other gender panel members. But today’s panel includes preeminent experts on this topic and I know they will share terrific and useful information. This size and significance of the impact of media violence from decades of vast psychological research from top academic institutions has been recently hotly debated. We continue to see an ever-increasing thirst for violence in entertainment media and exposure to violent pornography and differential media effects in different children. While we recognize limitations in the generalizability in lab research to real life situations, and that most children who are playing violent video games and viewing violence in the news aren’t perpetrating real life violence, there continues to be serious questions and a large void in longitudinal and naturalistic research studies which employ the latest novel technologies and methodologies. Our panelists have reviewed the questions that you have submitted and will answer as many as possible during their presentations. If you have additional questions during the workshop, please type them into the Q&A box at the bottom of your screen. When you do, please indicate whether or not you want to ask the question live on camera if time permits, or if you would prefer that the moderator read your question. We’re recording today’s workshop and had hoped to upload a video to Youtube in the coming days. All registrants will receive a link to our Youtube channel where you will find this video in the coming days and videos from our past webinars. It’s now my great pleasure to introduce our moderator. Doctor Dimitri Christakis is the George Akins Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington, Director of the Center of Child Health Behavior and Development at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Editor-in-Chief of JAMA Pediatrics and an attending pediatrician at Seattle Children’s Hospital. When he’s not being a brilliant pediatrician, epidemiologist, editor, researcher, he’s a close friend and advisor to Children and Screens. Welcome Dimitri.

Dimitri Christakis: Thanks Pam, wow that was a little more than I expected, it’s a pleasure to be here, it’s a pleasure to serve as a moderator for this very important topic, I do want to reiterate the disclaimer that Dr. Pam said at the beginning that some of the content may not be appropriate for children under the age of 18 and I won’t take too much time, I think Pam did a great job at setting the importance of this topic. I do want to add that we have an incredibly diverse and talented group of experts here, and rather than spend time introducing myself for the topic, I want to leave time for them to present briefly, each of them on their area of expertise, and then I promise we’ll have plenty of time for your questions, which I know is why you are here. And again, I want to reemphasize that the point of these workshops is to provide you with practical actionable advice to help you manage your children’s media, and most importantly to fulfill the mission of Children and Screens, which is to help children lead healthy lives in a digital world. Okay, with that, I would like to hand it over to our first panelist Dr. Douglas Gentile is a professor of psychology at Iowa State University and coauthor of Violent Video Game Effects on Children and Adolescents: Theory, Research and Public Policy. He is also a close friend, it’s a pleasure to have you here Doug. I’m turning it over to you.

Douglas Gentile: Great. Well thank you, it’s interesting to me that there is so much controversy around this issue, because great research has been done for over 50 years, here is one of the original classic studies back in the early and mid 60s

Video: Yeah Model pummeled the doll with a mallet, flung it in the air.

Douglas Gentile: So this is what children would see on a television.

Video: kicked it repeatedly, threw it down and beat it.

Douglas Gentile: And then children were released into a room with lots of different toys and just watch what they do, and it should be very little surprise that kids learned what they saw on the television, and then they copied many of those acts. So that’s one of the earliest studies, here is a more, a newer one, this is 3000 children measured 3 times across 2 years. And this is complicated but let me explain so the I is the intercept, it means what they did they start at the beginning of the study. So how much violent games were they exposed to at the beginning of the study. The S is the slope, how much did they change to watch violent, play violent video games over the 2 years of the study. Down here we have the intercept for aggressive cognitions. So we measured 3 types of aggressive cognition, the first one if you’re keeping track on your lucky psychological jargon scorecard is called hostile attribution bias. What this is is whether something annoying happens, do you assume it was an accident or do you attribute hostility to it, do you have a bias for attributing hostility to it. And of course, if you’re playing a violent video game, youre practicing your hostile attribution bias, you’re expecting things to come out and jump out at you, so it turns out that as kids play more violent games, they have more of a hostile attribution bias because they have been practicing that. The second type of aggressive cognition we measured is called normative beliefs about aggression. This is how acceptable you think it is to behave aggressively when provoked. And of course the whole time you are playing violent video games, you are usually getting rewarded for responding aggressively. In fact if you don’t respond aggressively many times you lose the game, so you get punished, so you are compelled to and then rewarded for behaving aggressively, which makes it seem more acceptable. And the third type of aggressive cognition is aggressive fantasies. Simply put, that’s how much time you spend thinking about how you would like to hurt other people. And of course, the whole time you are playing a violent video game, you are practicing and rehearsing aggressive fantasies. So what we see is that kids who start playing more violent video games, also start with all 3 of these types of aggressive cognitions at a higher level. If they change to play more violent video games, they change to have more of these 3 types of these aggressive ways of thinking. And, of course, the way you think leaks out into behavior. So as kids start thinking in these ways, they start being more willing to behave aggressively. Now what I love about this study is that it teaches us the truth about how this effect works. I want you to imagine that kid who has been spending a lot of time playing violent video games, and he’s at school. He’s in the school hallway. He gets bumped by another kid. Because he has spent so much time expecting people to be hostile, he no longer assumes it was an accident. That tiny little change of just expecting that the other kid meant to do it or wanted to make him annoyed, that changes everything. Another thing you practice in a violent video game is when you see an aggressive stimulus you quickly reorient you’re attention to it, so this kid will quickly turn to see the kid who bumped him, and will call to mind a response, what should he do. Now the thing that people do, particularly when under stress is the thing that comes to mind first. This is called the availability heuristic in psychology again if you are keeping track of your lucky jargon scorecard. And the thing that comes to mind first is the thing that you’ve practiced most. So if you’ve spending lot’s of time playing violent video games, you have practiced an aggressive response to an aggressive provocation, so that will come to mind. Now even that’s not enough to make him do it, because if he does it, if he pushes the kid back or he says something unkind then the odds that this might turn into a big fight skyrocket, but so there is kind of a high bar to get to to actually do it but because he is being rewarded thousands of times for behaving aggressively, that bar gets lower and lower, and so you can see how the odds have shifted in that school hallway that make him more likely to push back or say something unkind and when he does, if this turns into a big fight, here is the interesting thing, it looks nothing like what they were playing in games. Kids aren’t copying the violence, that’s not how this effect works, it’s much more subtle than that. It changes the way you perceive the world and the way you think and you take the way you see the world and the way you think with you everywhere and that just subtly shifts the odds, so that you are more likely to get into aggressive encounters over time. So that’s how this effect really works.

{Video: Supernanny Experiment on Social behavior.}

Narration: Each boy will be asked a series of questions. During the interview, Doug will intentionally knock a cup of pens over to see how the players respond. Will the violent players react in the same way as the nonviolent players. The first candidate for interview is one of the nonviolent football gamers.

Douglas Gentile: I’m Doug, have a seat. Just have a couple questions for you right now and then we might talk to you again in a little bit later on. Do you play games in your home?

Boy: Yeah.

Douglas Gentile: Yeah. What games systems do you have?

Boy: Just PS2.

Douglas Gentile: And what would you say are your 3 favorite games?

Boy: Do you want a hand?

Douglas Gentile: Sure.

Narration: Doug’s theory is that the nonviolent gamers will help but the violent gamers won’t. Jill is not so sure.

Jill: See, when Doug went to go pick them up, then the politeness kicked in and then he said do you want a hand. There was an immediate reaction, I know I think purely that was because he’s a polite boy, I don’t think it was because he played football. I’m not quite convinced yet.

Narration: So what happens with a boy who plays the violent war game.

Douglas Gentile: What are your 3 very favorites?

Boy: Call of Duty.

Narration: And another.

Douglas Gentile: And what would you say are your 3 favorite games?

Narration: And another violent gamer.

Douglas Gentile: 3 favorite games?

Jill: He didn’t even budge. He barely looked.

Narration: All 3 violent gamers have not offered to help, but what about a non violent gameplayer…

Jill: Nice.

Narration: …and another.

Douglas Gentile: And what would you say are your 3 favorite games?

Narration: So far all 4 nonviolent gamers have volunteered to pick up the pens. But what if we go back to the violent gamers?

Jill: So I think he gave less of a reaction than anyone I have seen.

Narration: Overall, only 40% of the violent gamers picked up the pens, but an incredible 80% nonviolent gamers all stepped in…

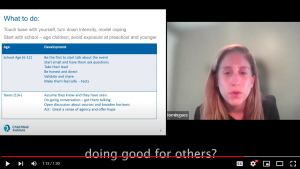

Douglas Gentile: So again, we don’t think of this as being one of the main effects of watching violent media but it changes the way they see the world, there was an opportunity to help and if they’ve been practicing being harmful to other people, they just didn’t even see that opportunity a lot of the time. Now what is it that parents can do? Well, we hear alot about ratings. The problem is the rating systems aren’t very good. When we ask parents in national studies, do the ratings on movie, TV, and video games give you the information you need, as you can see fewer than 1 in 5 parents thinks that they actually give them the information they need to be able to make an informed choice. And when we asked parents how accurate they are, only 6 percent at a maximum think that they’re always accurate. And so this is part of why parents don’t really use the ratings is because they recognize there are serious problems with them. In fact, it goes way beyond this actually. We’ve studied nationally what parents want to know, they want to know a lot, they would love to have detailed information, and when we ask parents what is the minimum age that kids can see, and we had 37 different types of specific content, parents never agree. And what this means is that if we assume that a rating is valid, if parents generally agree with it, but parents never agree at what age something is appropriate for kids, that means that age based ratings are always going to be invalid because a majority of parents will disagree no matter what the age is on them. So what can we do? Well, you first need to recognize, you cannot stop your kids from learning. The minute they see it they learn something from it. If you watch a TV show just once, and I ask you, what happened in it, you can tell me, there is no way to stop learning from the media. So you should learn and use the media ratings, even though they are not very good, still it’s better than nothing. But what’s better than that is going and actually learning from them yourself and nowadays it’s easy to find clips from movies, clips from video games, kids are usually off and happy to show you the worst parts of games, you can read online reviews and make your own decision, partly because well one of the reasons parents don’t agree what the minimum age is for things is because parents have different values. Some parents care a lot that their kids not see violence but don’t mind if they see sexual things and other parents are exactly the opposite. So this way, you have the power to choose based on what your family’s values are. So, thank you.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you Doug, that was fantastic. I do have one question from our audience and it’s a question that many of us hear and many of us wonder about in our lives. And that question is: What about mild cartoon violence, that a lot of children watch either as little kids or even as older ones. The sort of, superhero villain effect? Is it the same, different, should we allow that?

Douglas Gentile: Yeah, well there aren’t a whole lot of studies that directly tested. One that was done with my colleague Craig Anderson, we had elementary school children and college students come in and play a randomly selected video game. There was nonviolent ones and then there were violent ones, even at children’s ratings. And what do we mean there? The definition of aggression is intentionally harming another character who you could assume would rather not be harmed. So there are, you know, cute children’s games like one of them you’re like a spaceman with a ray-gun and you go around shooting other things, and it’s bright colors and happy music. And certainly when you shoot them they don’t scream in pain, and they don’t bleed all over, they don’t beg for their lives, they just disappear, but this would still count as aggression because you are intentionally making them disappear when you could assume that they probably didn’t want to be made to do that. And then the college students not only played these same childrens games but also played teen rated games that are kind of stylized, fighting games, and then other studies had them play the other photorealistic violent games. And after playing one of the randomly assigned games, we put them in another game where they think they are playing against another kid, and they can punish other kid with a very loud or long noise blasts, and these their maximum level are 105 decibels, which is about the same as me coming right next to your ear and screaming as loud as I can. It hurts, you actually watch people wince when it is that loud, so it, and you can set these levels for your opponent. And it turns out that if they play the violent game, it’s about a 40% increase in how many of these loud noise blasts they give. So they are behaving more aggressively, and that didn’t matter where there was cartoonish violence or the realistic violence. So at least, within a short term experimental context, where aggressive behavior is the outcome variable, there doesn’t seem to be much difference and at first I was surprised by this and then I wasn’t because once again this is about learning, what they are practicing. They’re practicing intentionally harming other people, and when they have an opportunity to, they’re in the groove. And if the question is about, say, desensitization as an outcome, then I bet how graphic and realistic, you know, how bloody it is, does matter. So it also matters what the outcome variable of interest is.

Dimitri Christakis: Thanks a lot. That was a lot to process but I think a very important answer suggesting that in fact as far as we know there really isn’t a significant difference between cartoon violence and real violence. In fact, if you look at the Bobo experiments that you showed from earlier, he found larger effects for cartoon violence for young children than non cartoon violence. Okay, our next esteemed panelist is Dr. Brad Bushman. Brad is a professor of communications at the Ohio State University, I guess I have to say that, and has studied violent media effects for over 30 years. In fact, Brad has been doing this longer than any of us. Alright, Brad, I’m passing it over to you.

Brad Bushman: Okay. So, I think this is the most important research that I’ve actually done in the last 30 years and I’d like to tell you briefly about it. First some deadly statistics. Although the US is only about 4% of the world’s population, US citizens possess about 48% of the world’s guns. And about 60% of US households with guns don’t secure them, or lock them up. And these households contain about 1.7 million children. Based on social learning theory, we know that children learn how to behave by observing and imitating the behavior of others. The people could be real or they could be media characters, even fictitious ones. And children are especially likely to imitate the behavior of others if they’ve been rewarded for performing those behaviors, and also if the behavior is a dangerous one and they’re not sure what the outcome might be. We know that children who see movie characters smoke cigarettes are more likely to smoke cigarettes themselves. And children who see movie characters drink alcohol, are more likely to drink alcohol themselves. What happens when children see movie characters with guns? They think these movie characters are cool. If they find a real gun, are they more likely to use that gun themselves? We know that gun violence in movies, at least in PG13 movies, has more than tripled since the rating was introduced in the middle 80s. So I’m going to tell you about 2 studies, the first one involves violent movies and the second one video games. We tested children in pairs, we gave them each 25 dollars, the kids were aged 8-12 and we told them that we were interested in what children do in their spare time: watch movies, play with toys, play with games. First we randomly assigned them to watch a movie with or without guns. The movies were rated PG so they’re age appropriate. Then we put them in a room that had lots of toys and games they could play with and we also had hidden cameras in the room so we could see what they were doing. In the room also was a real 9 millimeter handgun. Of course it was diabled and we modified it with a digital counter to count the number of times the kids pulled the trigger with enough force to discharge the weapon. And we hid it in the bottom drawer of a file cabinet. In many households maybe, gun owners might hide their weapons in a drawer for example. And we asked parents, parents were there, and they watched on hidden cameras with us what their children would do. And we asked parents, if your child finds a gun, would they tell an adult? 100% said yes, of course they will. But in reality, only 27% told an adult. We also asked parents, would they touch it? 100% said no way. When in reality, 58% did not touch it. So we timed the number of seconds they held the gun. As you can see, children who saw the movie characters with guns held it a lot longer than those who saw the movie without guns. Same movie, just with or without guns. And also, we counted with a digital counter the number of trigger pulls. Children who saw the movie with guns pulled the trigger more times than those who saw the movie without guns. So we wanted to replicate this, that’s how scientists gain confidence in their findings, and we did it with video games. We increased the sample size, this time we had 125 pairs of children. But the story was the same: we’re interested in what kids like to do in their spare time like play video games, play with toys, play with other games. The game we used was Minecraft, it was an age appropriate game. And the targets were these spiders and skeletons and zombies and creepers. And they played as this avatar on the left, and we randomly assigned them to play the same videogame, Minecraft, either with a gun and these targets, a sword and these targets, or there was a control condition with no weapons and no monsters. And they could play or watch the game, we flipped a coin. We got another gun because we found in the first study sometimes one child would monopolize gun play, so we bought another gun. And 2 digital counters, one for each gun. And once again we asked parents to predict what’s gonna happen if your child finds a gun. Will they tell an adult? 100% said yes, but only 22% actually told an adult. Will they touch it? 100% said no way, they won’t touch it. But in reality, more than half touched it, 45% did not. Once again we timed the number of seconds they spent holding the gun, you can see that it’s higher if they played a video game, a violent game with guns, followed by the violent game with swords, and the non-violent game was the lowest. And we also, in this study, because both children could have a gun, we measured whether they pulled the trigger of the handgun, and 966 children pulled the trigger, you can see especially if they played a violent game with guns. And we, in addition, we measured whether they pulled the gun while pointing it at themselves or at their partner, we tested the children in pairs. 36%, over a third, pulled the trigger of a gun while pointing that gun at themselves or at their partners. And they’re especially likely to do that if they played the violent video games with guns. In conclusion, previous research has shown that children who see movie characters smoke are more likely to smoke themselves, children who see movie characters drink are more likely to drink alcohol themselves. Our research shows that children who see media characters use guns are more likely to use real guns themselves, if they find those guns. So parents should protect their children from violent media containing guns, this is not harmless entertainment. And gun owners should secure their guns, they’re not toys, children shouldn’t be playing with them. Thank you. I think you’re muted Dimitri.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you so much Brad. I just want to emphasize that the work you presented here were experiments, so children were the same in each group, the movies they watched were exactly the same but you had taken out the guns in either the movie or the video game so it’s very compelling experimental research not merely correlational as some people ledged that a lot of the work done in this area is, so it’s frankly chilling to see the results of that experiment and I want to emphasize the importance of at a minimum keeping guns secure from children if you own them. So I do have a question from the panelist, I’m sorry, from the audience: and the experiments you showed sort of the short term effects, these are right after kids watched the video game, played the video game, or watched the violent movie. Did their risk of acting aggressively or playing with the gun increase. Can you comment a little about the long term effects because obviously many kids are doing this over extended periods of time?

Brad Bushman: Yeah, well, our study cannot shed light on the long term effects, only longitudinal studies can do that but you can think about, you know, if you smoke one cigarette, it probably won’t give you cancer. But if you smoke cigarette after cigarette, day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year, greatly increases the risk. So violent media can have this cumulative effect. And our own research has shown, we did a meta analysis where we looked at violent movies and video games, TV programs, and we show that these effects are larger for children than for adults. And the reason they’re larger for children, we propose, is that children’s brains are more malleable, they’re more easily influenced, they’re more susceptible to what they see than adults are. So if you look in longitudinal studies, you’ll find larger effects for children than adults.

Dimitri Christakis: Thanks Brad. Okay, our next panelist is Dr. Christopher Bartel. He is a Professor of Philosophy at Appalachia State University. He researches how players make moral decisions in video games and whether in-game moral choices have any impact on their real world moral values. I’ll pass it over to you now Chris, hopefully you can take over and unmute yourself.

Christopher Bartel: Excellent, can you hear me?

Dimitri Christakis: Yes.

Christopher Bartel: You can hear me? Excellent, good, thanks for inviting me. So, I’m gonna reiterate a lot of what our two panelists just said. A common research question that many people are interested in is: does playing video games, whether they’re violent or not, have any long term impact on the player? And there are lots of different ways in which you could look at this, you can look at this behaviorally, socially, you can think of this physiologically. What I’m interested in is whether there is any moral impact on the player. And morals are tricky, right, it’s hard to, it’s hard to quantify them, it’s hard to analyze them in a laboratory setting. So they’re a tricky one but the question I want to answer is: Does playing video games impact our moral character? One important thing to remember is that morality is not something that you’re like magically, innately born with. It’s something that you practice, you develop it, you have to actually work at it. Your moral character is that unique set of tendencies, habits, beliefs and values that a person has. And to get those, it’s something that you actually have to work at, you have to practice. The 18th century Scottish philosopher, David Hume, made this really fun quip. I don’t know how seriously you should take this quip but I really like it so I’ll tell you about it. He, David Hume, makes this point, he says, you will have the face that you deserve by the age of 50. And what he means by that is he’s actually talking about the way the wrinkles on your face set in. And his idea is that if you are a jovial, happy person that smiles a lot, you’ll have smile wrinkles and you will have a happy-looking face. If you are an angry person and you’ll scowl a lot, you’ll have scown wrinkles and you’ll have an angry-looking face. The idea of it is, the way that your face behaves, it kind of sets in. And take that actually and seriously in morality, it’s something that sets in, something that you practice; that if you practice being an angry person, you become an angry person. If you practice being a compassionate person, you become a compassionate person, it’s something that sets in as well. Morality is based on these internalized habits that ultimately shape our future actions. Last year I wrote a book on this, yay for me, and one of the key things that I was interested in, in the book, was how to deal with skeptics. Because a skeptic is somebody who thinks that morality has really nothing at all to do with video games because they’re not real, because it’s just a game. When I’m running over pedestrians in Grand Theft Auto, I’m not running over anything that’s real, so why should I morally care about this? The thing to remember is that the skeptic is half right. You can think of morality, broadly speaking, as having two components to it. One component is your actions, it’s what you do. But the other component is hidden, it’s this thing that’s hard to quantify, it’s hard to analyze, it’s the hidden part of: judgement. That not only do I act in certain ways, but I also judge in certain ways. I judge that I have a duty to do X, or I judge that I have an obligation or I judge that something is good or bad. Teaching somebody to be moral is not just teaching them to act in the right way, but it’s also teaching them to judge in the right way, to feel in the right way. What’s interesting to me about video game ethics is the point that what happens in a video game is fictional, it’s not real. And that’s totally true right? Your actions are not real actions. But what’s interesting is that your judgements are still real judgements. I really am using my moral sensibilities to judge what I should do in the game, what I shouldn’t do in the game, whether what in the game is happening is good or bad. It’s still my real sense of morals that I’m applying or employing within the game. So, the thing that excites me about video games is that you can kind of think about them as moral practice spaces. We train ourselves to develop moral habits, that’s the broad concept of moral development. And you can actually use video games as ways of training yourself, of making good and bad decisions. I’ll be honest, I’m a gamer myself. I play quite a lot of games. And I would defend the idea that there’s a place for violence in games for players that are mature enough to handle it. Like great art, like literature, films, like good TV, we want a range of stories that covers the whole gamut of human experience. We want stories that handle tragedy as well, right? And one of the things that I like about some games is that they enable me to think about tragedy in interesting ways. So I would suggest that, for mature players, games can be this interesting place where, they offer a powerful tool for moral reflection. But that only works when the game is well-designed to do so and the player takes it seriously, and those two things usually don’t line up. Many games are not really well-designed for moral reflection and mplayers really don’t take it seriously, in which case it falls flat. I look forward to a future where games are better designed and players are more serious about it. But for now, I can offer you a couple of suggestions. Thinking about kids’ moral development and video games. I know it’s really not easy to think about, I have a daughter myself, she’s 8 years old. And what we do is, we talk a lot. We have really deep conversations often about stuff that she watches and games that we play. And when we talk, I can get her to have really deep thoughts about morality and the trick is about asking the right questions. So I start with questions like what does a good person do? And what would a good person do in this situation? And what is challenging about this situation for a good person? And you know we have really deep conversations about these things, they’re not long conversations, she’s only 8 after all. But we have great conversations. We talk about the morality of the games that we do play, whether it’s real games, whether it’s board games, whether it’s video games, whether it’s playing out in the yard. We often start by talking about what the story is. We ask why are the bad guys bad guys and could they make better choices? There are lots of other ways that you can use games to help children with their moral development. Team sports, I realise that talking about team sports when we’re all quarantined is ridiculous, but you know, in the before times, when we were not quarantining, there was this thing called team sports. They’re actually a fantastic way of developing sportsmanship, which is this really interesting moral value that you can use to build on other values. Literature, obviously, is a great place to get kids to think about morality and one of the things that I do with my daughter is that we take a story and we make it into an imaginative play. And also I know we’re all quarantined, so your kids are playing a lot of video games. I would point out there are lots of video games that are not violent games, that actually do give kids a really great place for kids to practice thinking about some kind of ideas. There are really great cooperative games, there are puzzle games, there are games that I would refer to as like digital doll houses, and those are actually great places for kids to start practicing the person that they will become. So thank you again for having me.

Dimitri Christakis: Thanks Chris. That was great. I do have a, I have a question, again, from the audience. Is there in your opinion a difference between real violence, you spoke about video violence and video game violence, but what about the real violence that children are seeing either on TV or on the internet? We live in a world now where we see real violence streamed on FaceBook or on television. Are the effects different in your opinion? Should we be more worried about those? Those conversations.

Christopher Bartel: That’s a really interesting question, I’m glad, whoever asked, that was a great question. Thinking about the moral point of it. Think about the distinction I offered before, between action and judgement. Whether the action is real, morality is subtle. Morality is always contextual. We always make moral judgements within a certain context for certain reasons. One of the things that we take into account when we make a moral judgement is about whether the action is real or not. So that certainly has to do with our actions, but the interesting thing is about judgement. The judgment itself is, I’m actually still using my real world sense of morality whenever I’m making any sort of judgment, and actually it doesn’t matter whether the action that I’m seeing happens to be a real action or happens to be a fictional action, I’m still employing or I’m still using all of those moral sensibilities that I’m really using in a real world sense, so in a way, no it doesn’t. Thanks again.

Dimitri Christakis: Alright. Our next panelist is Dr. Desmond Patton. Desmond is an Associate Professor of Social Work and Associate Dean of Curriculum Innovation and Academic Affairs at Columbia University, and he is the Founding Director of the SAFE Lab, which investigates what social media posts can tell us about violence. I’ll pass it over to you Desmond, you can unmute yourself and share your screen.

Desmond Upton Patton: Okay, good afternoon. It is so good to be with you all. I’m Desmond Patton and my research is at the intersections of social media, artificial intelligence and gun and gang violence. And also, by way of introduction, I define myself as a social worker first and a public interest technologist who is interested in the role of artificial intelligence and social media and understanding the epidemic of community based violence. The work that I do is motivated by the epidemic of community based violence particularly in the city of Chicago. This city as you probably all are aware, is constantly in the news, it has many uptakes in violence. In the last five years, it has seen upwards of 50-60% uptake in violence, particularly in the areas of homicides and shootings, but not in physical altercations. In addition, as you can see on the map, violence is concentrated on the South and West sides of Chicago, which are predominantly Black and Latinx communities. So there’s always a lot of concern and worry about the continuous issue of violence in the city. And at the same time, young people are spending an enormous amount of time online. These are some statistics from the PEW research center which (shows) young people are living their lives online, sharing all aspects in terms of communication, public life, and school life and home life, relationships gone wrong and pain and trouble and love and joy. This is a central part of youth development but oftentimes we are not considering the way in which social media is not this virtual thing that people do when they have free time but perhaps we should consider it as a new environmental context, a new neighbourhood, a community in which our young people are living. But what is happening is that there’s a confluence between community based violence and gun violence and the use of social media in which taunts and threats that are communicated, that would normally happen in the school yard, in the neighbourhood, are also happening on social media. And so we’re seeing the everyday lived experiences with trauma and grief and gang violence that are now amplified through social media platforms. And so, in 2012, there was a big blowout between two very well-known rappers in the city of Chicago both from the Southside and from rival gangs. One of those rappers was fed up with the back and forth on Twitter and decided to post their location on Twitter, and within 3 hours that individual was murdered in that exact location. And so I became really worried and fascinated by the role that twitter played in accelerating or amplifying that particular event. I went to the literature and there was absolutely nothing there really about the role of social media. And so with colleagues with University of Chicago, we coined the term internet banging and wrote a conceptual paper that sets parameters around this new phenomenon. Essentially, internet banging is a play on words on gang banging and we define it broadly as using social media to trade insults or make violent threats that might lead to offline violence. And we think of this as a cultural phenomenon that has evolved from the increased use of social media, but also representing an adaptive structuration of this media, meaning that it is an unintended design of the platform that we are now seeing proliferate on social media platforms. To drill down on this concept of internet banging, I started small. So oftentimes in data sciences or artificial intelligence, the idea is to go big and have big data approaches. But, there was a story that evolved in 2014 that was like no other story and this was the story of Gakirah Barnes. Gakirah was a 17 year old young girl who was murdered just blocks from her home on the South side of Chicago. What the media presented was a young woman that was called the gun-toting gang girl of Chicago. She allegedly had shot or killed 20 people by the time she was 17 years old. And she was one of the only young women that was called a shooter or hitter in her gang from the South side of Chicago. And so she was unlike any other, and left this really robust and complicated and dense Twitter profile that I have been digging in using artificial intelligence tools for the last 6,7 years. Other things important to note was that she was quite active on Twitter. She had almost 5000 followers and over 27000 tweets, which put her in the 96th percentile of Twitter users at that particular time. So, I wanted to understand a couple of things. Gakirah was murdered April 14th, 2014. And so I really wanted to understand how people would react to her death, people in her twitter network. And if there would be any signs of retaliation. And so, I looked at her Twitter profile and also individuals who would be deemed her top communicators. And what we found was plenty of Twitter posts that might be identified or interpreted as violence, right? So posts about invisible gun lines, posts that could be interpreted as threatening towards oppositional gangs on the South side of Chicago. But that was a particular fring that was formed by negative views about Gakirah and other young black children. What Gakirah did in death, for me, is that she showed me a very different young girl. She problematized her life by showing deep pain and grief, and things that I wasn’t initially looking for because I didn’t see her as a whole person. I didn’t see this young person as a child who also felt pain, who also experienced more death than probably anyone that we probably know. She said things like my struggle aint be told and the oops killed my bro, using heartbroken emojis, things that you wouldn’t see or expect to see from someone that you might deem a bloodthirsty killer. As a part of understanding this story, it is integral to understand the language and the context of that story. And so what became very clear in looking at Gakirah’s tweets and tweets from other young people in her community is that we didn’t know what the hell young people were saying online. We didn’t have the tools, we didn’t have the context to interpret language and context in emojis. And so we developed a methodology called CASM, which is the Contextual Analysis of Social Media approach. And the goal of this approach is to be a labelling process for the annotational social media data that can then be used for algorithmic systems. And so here, we prioritize looking for context, looking for engagement, looking for any outside events that might help us to understand how to contextualize these posts. We look at the network, right, a young person may claim or identify gang affiliations but then be following Disney characters, so really trying to understand who they are and before we label a post, how much context is useful and helpful to have to be able to pick the most accurate label possible. And so this CASM approach is a 7 step approach that forces us to reckon with our own bias, our own issues with racism and how we view the language of young black children. The critical bit to this piece is going back to the community and asking young people, do we know what we think we know? Are we interpreting these posts correctly? Are we translating these posts correctly? And, are you okay with us doing this? And so, as you might imagine, there is a huge ethical component to this work where it’s important to understand that the use of AI and social media to look at the lives of young, Black and Latinx children can be misused, particularly if we are misinterpreting these posts. So what these young people do, some of whom are formerly gang involved or at the time were currently gang involved, they helped us to understand the role of social media, they helped us to unpack context and they helped us to think about whether or not we are looking at this with the right lens. And so the objective of this annotational CASM process is to develop an artificial intelligence system that automatically detects aggression and loss in social media posts that are gang-involved. We use Supervised Learning and Natural Language processing and then more of a Neural Net approach to look at the word embeddings within a particular Twitter post if you will. So what does this all mean for how you talk to young people? And I think the thing that I’m hearing come across is to talk is to have conversations, to have critical conversations right? See, it’s important to have open dialogue. Young people are going to see negative things on social media. They may even post negative things, but if we are not talking to young people about their social media life, if we’re not talking to them about what they’re seeing, if we’re not asking them questions about who they’re following and why they’re following them, then we’re gonna miss whole swaths of what’s happening on social media. What’s been interesting is that I’ve been talking to Gakirah Barnes’ mom for a book that I’m writing, and what she kept saying is that I knew what she was posting online. I talked to her about what she was posting online, I told her to take those posts down, and yet she continued, right? And so there has to be more thought and more conversations that go beyond just conversation, but what do we do next? Should you put privacy settings on your child’s phone? Should you take the phone away? What are the non-negotiables for the relationship your child should be having with their social media accounts? And I think that’s a personal conversation between the parent and the child as well. Here are a few resources that you might want to consider for thinking about safety online, and then if you are more interested in some of the direct comments that we have, you can look at our article in the PEDIATRICS called Youth Gun Violence Prevention in a Digital Age. Thank you.

Dimitri Christakis: Thanks Desmond. That was great, and really very compelling. I’m gonna ask you to answer the question you asked yourself, which is what should your parents do? I mean we don’t have access to CHASM, maybe we should for our own parenting purposes. Can you give some practical advice to parents? Should they be following their children’s Twitter feed, should they be on their Instagram, should they be looking at what they’re posting? And it sounds like at least with Gikarti’s Mom, that didn’t make enough of a difference. So what is the practical advice, I mean, you said, you asked these questions but you didn’t give any advice.

Desmond Upton Patton: Yeah because you know, I’m a social worker and I really believe in trust-building between parents and their kids. And so, I am apprehensive to say surveil your kid or take the phone away without having these open and robust conversations. And so I think the first strategy, I think, is to know what your child is doing online, to be aware of the environment, and to first also tell yourself that this isn’t just something that they do on the side. Probably now, young people are spending an enormous amount of time online and that social media can be a source of support and well-being and joy, but it can also be problematic. So there needs to be an awareness piece that happens first, but I think you have to, I think you need to build trust with your child to actually have these critical questions. Now, in the case of Gakirah, there were a host of macro-issues that made this situation very complicated. She lived in a neighbourhood with high rates of community violence, her mom was always battling the environment outside of the home. And so, if that is your situation, then you need additional support and resources to help you manage that particular situation.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you. Okay, our next panelist and last but certainly not least is James Densley. James is a Professor of Criminal Justice at Metropolitan State University, part of the Minnesota State System, where it’s quite cold now I imagine, and is co-founder and co-president of the violence project research center. Alright James, please take control and unmute yourself and start your video.

James Densley: Okay. Hopefully you can all hear me and see me. Thanks so much for hosting this event, for inviting me to be here. Dmitiri, thank you for moderating and thanks to the fellow panelists for their work. This is a tough act to follow, and it’s really an honor to share this virtual stage with you all. So I’m a sociologist and a criminologist, and there are two streams to my research on social media, and I’m just gonna talk to you all. I’m not gonna share any slides. But the first stream of this research looks at the role of social media in the lives of mass shooters and school shooters. This is a part of a study that was funded by the National Institute of Justice. And if you are interested in learning more about it, you can go to theviolenceproject.org to learn more. But we’ve interviewed incarcerated mass shooters, and the people who know them, their parents, friends, family. And we’ve also built a database of mass shooters, that includes those who post on the internet and on social media before or during a mass shooting. And what we find is that mass shooters study other mass shooters and this contributes to the spread of mass shootings. Many people experience social and psychological strain and they ask themselves, how have others like me chosen to deal with it in the past. Who is more similar to an angry young man in crisis than another young angry man in crisis, and seeing what past mass shooters do and what other school shooters have done, whether it’s posting a manifesto, or wearing a trenchcoat or using a certain type of assault rifle, provides future mass shooters with proof of concept and it’s a model of behavior, and you see social media creates an illusion of proximity for these individuals to the extent that if you will the objects in the twitter view mirror may appear closer than they really are. Social media extends our in person interactions, and increases the frequency, duration, and intensity of our real life communications. It also increases exposure to online only associations and this can introduce what criminologists would call definitions favorable toward violence. Now this is especially true in the other line of research that I have, which is focused on how, a bit like Desmond’s work, gangs and gang members use the internet. Now using a mixed methods approach, which includes qualitative interviews with young people in gangs but also content analyses of gang related content, we find that social media provides incentives to perform either to win the internet or to save face. Visual platforms like YouTube or FaceBook Live are driven in large part by spectacle, and they have in turn made it in turn easier for someone to make a spectacle of themselves, and in the social media age creating a continuous stream of gang-related content for consumption has become of the duties for gang membership. The fact that gang reputations can now be quantified by the number of followers, likes or retweets that one receives, actually creates incentive to do gang, to perform gang membership and this raises the prospect that gang members are taken in by their own act. They find themselves unable to break character when out on the street, and that can actually lead to real world violence. Now in the natural world, if you want to protect yourself from predators, you get big and scary. Social media affords gangs that same illusion of size, strength, and spread. And I think the key point here, and this is very consistent with what Desmond was just talking about, is to not take all the claims at face value, unduly criminalizing actions that everyone on social media is guilty of…portraying their lives as more glamorous or dangerous or exciting than actually are just for the sake of retweets or likes. Like Desmond said, context matters, especially when some of this posturing can actually help diffuse tensions and de-escalate violence. But, my research has shown that there is definitely a darker side to the violence, performances that we see online. Mass shooters, for example, now live stream their massacres. During the 2017 attacks at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida which killed nearly 50 people, the shooter checked social media to make sure that the massacre was going viral, and it was. Here posting and videostreaming are integral to the violence itself. It’s not incidental to the crime or some horrible personal trophy that the shooter will relive later. Some of this is about fame seeking, but it’s also about feeling part of something bigger. And that’s what brings me to those who commit violence in the name of hate. What we find is that extremism is less of an ideological movement and more of a social one. Some clearly are more invested in hate than others, but what all these individuals have in common is that they’re searching for something to make sense of their lives. No one living a happy and fulfilled life will go searching for answers in the darkest corners of the internet, and not everyone finds who or what lives there equally compelling. The internet helps facilitate violence for some of these people, it enhances it for others but either way we have to take a step back and ask ourselves, why people select into this type of extreme violence in the first place. So here are some of the takeaways from my work, whether it’s hate groups live streaming their storming of the United States Capitol, or a mass shooter, or a gang related incident, we must always ask ourselves, how are these events being packaged, much like we do for traditional media. We have to recognize that what we see on social media is not representative of the entire universe of observations. There is always a selection bias, but this also means that we are competing against persuasive design techniques, push notifications, endless scrolls on our news feed, which capture the hearts and minds of users and create a feedback loop that keeps us glued to our devices. As parents and as educators, it’s a bit of an unfair fight because social media platforms are designed to profit from a form of confirmation bias, a natural human tendency to seek, like, and share new information in accordance with our preexisting beliefs. To keep us online, they rely on adaptive algorithms and assess our interests and flood us with content that is similar to what we’ve liked before. And this makes it really difficult for extremists to kick old habits like extremism, or for gang members to get out of the gang. If someone wants to avoid the gang or hate or violent mass shooters online, personalized search results based on our past click behavior and our histories create what experts call filter bubbles’ that make these things somewhat unavoidable. The social media echo chambers provides a reaffirmation for this violence and hatred. It silences outside voices and it contradicts many interventions and the countervailing messaging that they provide. These algorithms are designed to promote outrage. It amplifies the biases within the data that users are fitting them. And in turn when we are forced to watch unedited, and unpredictable, at times horrific acts of violence, on a continuous loop, autoplaying in our feeds, we are experiencing some form of secondary and vicarious trauma. This is especially true for some gang members for whom violence is really in their day to day lives, in real life, not just something that they see on social media. It creates a sense that the world is unsafe. This in turn could make people pick up guns for the sake of protection. It also gives us an elevated sense of our own risks of violence or violent victimization, which is clearly not very healthy for us and our mental health. So what can we do about it in the 30 seconds I’ve got left to talk about it? I think the key takeaway for me is we really need investment in young people’s cultural awareness and media literacy. They need to be asking, who created this content? Was it an individual, was it a company? What are their qualifications? Why did they make it? Who is the message intended for? What techniques are being used to make this message credible or believable? What details are being left out and why? And how does that message make you feel? And I think with greater media literacy, a more critical interpretation of the content, we can help break down some of this violence. Thanks.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you so much James. That was great. We actually, we do have for you as we transition to the question and answers from the panel, we do have a live question and so here is the question for you. Hopefully, we can make this work technically. It’s from (*Sonia Detweiller* blur out for privacy), I hope I’ve pronounced your name right. Sonia, are you gonna come online and ask your question?

Sonia Detweiller (audience-member): Hi, can you hear me? Hi, well first of all I just want to thank everyone for being here and promoting this wonderful, not wonderful but very important topic. I’m really learning a lot so thank you for that so thank you for that. I have a question for whoever wants to answer. What is the best approach in your opinion to get schools, I’m talking public K-12 schools to understand that social media is not designed for kids and to not encourage them to be on it because I think some of the parents are thinking it’s safe because the schools are promoting it. Just about every school website I’ve seen has a Twitter feed. Come join us on Twitter, or Instagram, or FaceBook. How do we change that shift so that schools are now educating the parents and students that this is not a safe platform for our students?

James Densley: Thank you. It’s a very important question, and I’ll just say in my response to it, so in a previous life, before I became a college professor, I was actually a middle school special education teacher, and so I used to work in the NYC public schools, and so at that time social media was just becoming a sort of a new phenomena, and we were starting to grapple with some of those questions ourselves. Also in the mass shooting and school shooting work, I do a lot of work with schools. And this is definitely at the top of mind. I would say this: a lot of this is about meeting young people where they are, and where they are is they are on social media, and their lives are, you know, intertwined. I think as Desmond really articulated well in his presentation, is you’ve got online worlds and offline worlds, but they are not mutually exclusive, they really bleed into each other, and I think we really have to recognize that in this work. But I do think your point is correct that these tools were not really designed for children, and they have a negative impact on them. Now if you ban something, it only makes it more appealing. So in some ways, we have to really focus on how social media is working, and give young people the tools to better interpret how it’s working. It kind of goes back to what I was saying with sort of digital media literacy, when we think about these tools. This is especially important when we think about cyberbullying, and people posting online threats and other things because we want to create an environment where students feel safe to talk about these things and to share content with adults and appropriate individuals and I think that is important. And then the other piece I just want to mention is you know we got to recognize that not all screen time is created equal, and there are some things that can be done positively with social media, but only if we fully understand it and if we give young kids the tools to navigate it appropriately. They really have to understand that it is a dangerous space, which is why we have to kind of think about things like limiting screen time and other things as well. But we don’t want to criminalize the use of it, because we want to create an environment where young people feel like they can talk to adults about what is going on on social media so it doesn’t get sort of hidden and placed away. And I’m sure I’m over time, so thank you for your question and I’ll hand it back to Dimitri and the panel.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you very much James. So panelists, you’re all professors. You know how to raise hands, so I will start asking questions of one of you, and if anyone has anything else they want to add, please raise your hand. I’ll call on you as many times as I can. So we got several questions from the group about this issue of catharsis, and I like that question because catharsis is actually a Greek word. Aristotle used it first and it means the act of purification that. And the question essentially is what about this concept of catharsis? Is there any truth to the idea that you can get your violent aggressive thoughts and emotions out playing violent video games and be less violent in the real world? I think I know the answer but I’m going to start with Doug. Doug, you didn’t raise your hand, but I’m calling on you. Go ahead, and if anyone wants to add on, please raise your hand.

Douglas Gentile: Well I think Brad should add on because he has done some great studies on this. But you point out Aristotle and it means to purify, not to get rid of. You are exactly right, which is an interesting thing. So he didn’t actually say, and he was talking about media violence by the way in poetics. He’s talking about plays and poetry, and music, media of his time. And he doesn’t say it gets rid of it, what he is trying to do is make man moral. Right? So finding the mean, so showing you the extreme you learn how bad it is, that’s not what’s happening in modern media violence. There are several problems with the issue, one being we are misusing Aristotle. But, another is my studies, the kids can come, play, be randomly assigned to play the violent game and be less aggressive, they are designed to show that, the kids just never are. Sometimes there’s no effect. But when there’s an effect, it’s pretty much, always they’re more aggressive, so the data don’t support it, and beyond that that is not how the brain works. How do you memorize a phone number? You repeat it, right? Does seeing it one more time take it out of your brain? No it burns it in deeper. Each time we see it is one more learning trial. There is actually no possible way for catharsis, meaning to remove it from you by seeing it, to work. But Brad has done some studies that really looked directly at this, and I think he should tell you about them.

Dimitri Christakis: Alright I’ll let you make me do my job. Professor Bushman, I’ll call on you now, I’ve seen you’ve raised your hand. Go ahead.

Brad Bushman: Yeah, well Catharsis Theory sounds good in principle but there’s not a scientific shred of evidence to support it. So the theory proposes that by behaving aggressively or watching other people behave aggressively then you’ll be less aggressive yourself, but the opposite like Dr. Gentile said, the opposite is true. Observing violence actually makes people more aggressive. It keeps the aggressive thoughts active in your memory, it keeps the feelings alive, it keeps the arousal levels high, you know? It just sets the stage for more aggression later.

Dimitri Christakis: Thanks. Alright the next question, Desmond is for you. And you talked a lot about the rise of gun violence in Chicago, which of course, is extremely troubling, but you also mentioned that interpersonal violence in Chicago has gone down. In fact, it looks like trends across the US and Canada are for decreases in overall acts of extreme aggression. And the question, or several questions from the audience, asked if you could, you, and the panel in general could raise their hand, how do you explain that? Right, if violent media is really affecting violent behavior, why are we seeing at least in some communities decreases in violence in spite of the fact that children are consuming lots of violent media?

Desmond Upton Patton: Yeah, that’s a great question and I don’t have an answer for you. I think that a lot of people, particularly in Chicago, have been trying, have been pulling their hair out trying to understand why there’s been a decrease in physical alterations. I guess the prevailing theory is that we’re not spending as much time in public spaces in the way we used to, and so when young people would go to the mall or spend time after school, that time has decreased overtime and it has moved to more online spaces. But I think that I haven’t seen a definitive answer as to the reason why that’s happened yet.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you. Prof Bushman, you’ve raised your hand, unless you kept it up from before. Oh, you just, you took it down. Okay, excellent. Alright, let’s see.

Brad Bushman: I think Doug’s hand is up.

Dimitri Christakis: Oh, his real hand. I was looking for the fake hand.

Douglas Gentile: No, I have a real hand.

Dimitri Christakis: I…yes, Doug sorry.

Douglas Gentile: So, there are lots of answers to this. One is that we’re using sociological data such as crime statistics to try to understand the psychological level and individual level effect and those really aren’t the same types of data. But another way of thinking about it, this is my metaphorical aggression thermometer, and down at the cold end, kids are always respectful and polite, I’m sure this is all of your kids and as it heats up, they might have you know have some aggressive thoughts or say some unkind things or do relational aggression like I’m going to a party and you’re not invited. Only when it starts to get really hot does it even get up to anything physical like pushing or shoving or only at the very extreme, you know criminal level violence. And so we’re using crime statistics, which are the most extreme thing to try to understand an effect that is happening much lower than that. So if we take say the killers at Columbine High School…well those kids had uninvolved parents, and so we can, you know add a little there. Those kids had psychiatric illnesses. Those kids were bullied. Those kids also consumed a lot of media violence. Is that the thing that pushed them over the edge? That you know, that’s the straw that broke the camel’s back? I don’t think so. But the point is that there are over hundred scientifically documented risk factors for aggression, media violence is just one of them. It’s not the biggest, it’s not the smallest, it’s about the same size as coming from a broken home, and most people who come from broken homes don’t do criminal level aggression. That didn’t make it okay for them though. That didn’t mean that it wasn’t still a risk factor and the flip side is every protective factor cools it back down, and most kids have some protective factors, so that means no matter how much media violence they consume, it’s not going to get all the way up to the level of violent rather than aggressive behavior. And so where would we see the effect, we should see the effect at the low level aggressive behaviors, what I would sometimes just call playground level aggression, and if we look, that’s there. You know, so in one of the big school shooter years, there were 35 deaths in schools, as horrifying as that number is, it’s just the tip of the iceberg. 250,000 times, you’ve got the kid to the hospital in the time he didn’t die. 1,000,000 thefts or larcenies. 1,000,000 have reported fights in schools, and 18,000,000 incidents of bullying. If I’m right that media violence is heating it up for every kid, where would we see it? We’d see it at the low level aggression, not at the most extreme because to get to the most extreme requires you have many risk factors, not just the one, and almost no protective factors, and most kids have a few of those.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you, wow, looks like you were prepared for that question there Doug, you’ve got slides and everything. Wow.

Douglas Gentile: I knew it would come up.

Dimitri Christakis: Okay, I’ll put this question out to the…well, actually, I’m gonna call on James first because you haven’t answered in the session here yet. James, how…what are parents supposed to do with all of the real violence that they’re seeing in the news these days, I mean for example the Capitol Hill insurrection. They were horrific real world violent acts perpetrated, and they were real right, this is the news. How should parents handle that and what they do with respect to discussing with their children, allowing them to see, in fact it’s kind of on auto loop on so many social media sites you’re exposed to repeatedly.

James Densley: Yeah, and I think actually that the latter point you raised, Dmitri, is what I wanted to really stress, which is in the social mediated world that we live in, it’s hard to ignore these things. That the expectation is that students, that young people will see them. And if they’re going to see them, I think we want to be as the adults in the room, ones that help them interpret those things. And you know, it’s a bit cliche to say, use it as a teachable moment, but you think about the Capitol riots, you know just thinking about well let’s talk about what is the symbolism of confederate flag, what is the symbolism of Nazi propoganda you’re seeing, why are people doing the things they’re doing? These are all things we could use to educate young people about the surge of white supremacy and hatred and the rise of this type of violence in our society, and use it as a teachable moment in that sense, but I think it has to be sort of guided by us as adults. And then the one last thing I want to stress with that as well is we as adults have to be modeling the right response to this stuff as well. So if we have it on in the background constantly, on constant loop on the news, and if we’re fixated with it and obsessed by it, and we’re getting stressed out by it, the emotional contagion in the household is that the young people are going to be experiencing that too. And so switching it off, and having a bit more of a you know a targeted and focused conversation about this stuff and a more informed one is the way to go about it. But just to expect it to disappear and that young people won’t see this stuff, I don’t think is the right way to go because unfortunately it’s everywhere and they’re going to be exposed to it, so we have to, we have to be mindful of that.

Dimitri Christakis: Thank you. Chris, I’m going to ask you a question. You know, you talked…I think of all the panelists, you were the one that talked of the, at least the potential upsides of, actually I think you’ve even talked about the upsides of (unintelligible) playing violent video games. But I wonder if you could talk about…are there games that you would actually recommend, that you feel are, that create pro-social spaces and that actually might be…that might counterbalance some of the extreme aggression that children otherwise engaged in? And I’m not gonna put you on the spot here, but I’m sure the moment you start this, parents are going to want to know precise recommendations if there are any in particular you want to endorse and I won’t ask you now unless you are comfortable but we will ask you to provide some resources later for our website.

Christopher Bartel: Yeah, I can mention some. You know it’s tricky when you’re thinking about different age groups. You know, there are interesting games for mature players that are, you know, college-age games, college-age students that I would, you know, recommend but you know, if we’re thinking about kids around elementary school, one really interesting game is, my daughter loves playing, it’s called Little Dragon Cafe. And what she does is she runs a little cafe and she serves people meals. And she absolutely loves this. It’s the kind of game that I think of as sort of like a digital dollhouse, that what you’re doing is you’re taking a character and you’re dressing it up like a doll, and you’re taking it on little adventures, and, you know, she gets really invested in the happy little lives of her Dragon Cafe. Animal Crossing is an interesting one, there isn’t any violence in it. Bad things don’t happen right? For every game I could mention, there are also little critiques that I could give. I won’t bother, like Animal Crossing is also an interesting way of teaching kids about mortgages, which isn’t the most exciting thing but there’s that one. A game that, we also really like puzzle games. A game that we really like is an oldish one called Thomas Was Alone, and it’s a fascinating game that has very little visual information but the characters that you have are just little cube of blips that develop these really intense personalities and just being able to see a personality in this very abstract thing is fascinating. And, you know, one of the things that is interesting, at least morally speaking, about that is that it actually helps kids develop a sense of sensitivity of being to project feelings onto other beings and that’s, morally speaking, very useful.

Dimitri Christakis: Thanks. I really want to thank all of you, we’re running out of time here. This has been an extraordinary panel. I’m sure that we didn’t to get to all of the questions, but I just want to emphasize for parents, that the most important thing that you should takeaway from this is that it is really is important to be engaged with your children’s use of digital media, to be intentional and thoughtful about it, and to capitalize on what Chris just said, that there are ways that you could actually make it a positive force in your childrens’ lives, and that’s really the mission of Children and Screens. I want to pass it back to the President of Children and Screens for some final thoughts. Pam, it’s back to you.