Parents worried about child media use may not be aware that their own media use patterns at home may be significantly affecting their children. In this episode of Screen Deep, host Kris Perry discusses “technoference” – the interference of technology in relationships – with the researcher who coined that term, Dr. Brandon McDaniel. Dr. McDaniel shares results from his work on how parent device use can affect relationships and impact children from infancy through adolescence, how children may manifest these impacts through behavior, as well as how parental mental health and stress inform and are informed by their own technology use. Dr. McDaniel discusses the challenges of limiting phone use, and provides suggestions for how parents can model healthy device use during family time, work to be more present in interactions with their children, and manage co-parenting conflict around family media use rules.

Listen on Platforms

About Brandon McDaniel

Dr. Brandon T. McDaniel is a Senior Research Scientist at the Parkview Mirro Center for Research and Innovation, Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine Fort Wayne, and internationally recognized expert on the impacts of technology use on relationships, families, and children. His research has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, and he has published more than 80 scholarly articles related to technology use, parenting, family relationships, and more. He also regularly engages in community education in the promotion of healthy digital habits.

In this episode, you’ll learn:

- What “technoference” and “phubbing” mean.

- How parental technoference affects children of all ages.

- Behavioral signs in infants, children, and adolescents that may indicate negative effects of parent media use.

- How parent stress and mental health influence media use and impact children.

- Early findings from an ongoing research study on parents of infants and the connection between their media use and mental health.

- Where the research is going to better understand the complex interplay between parent media use, child development, and behavior.

Research papers, in order mentioned

McDaniel, B. T., Pater, J., Cornet, V., Mughal, S., Reining, L., Schaller, A., Radesky, J., & Drouin, M. (2023). Parents’ Desire to Change Phone Use: Associations with Objective Smartphone Use and Feelings About Problematic Use and Distraction. Computers in Human Behavior, 148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107907

McDaniel, B. T., & Radesky, J. S. (2018). Technoference: Parent Distraction With Technology and Associations With Child Behavior Problems. Child Development, 89(1), 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12822

McDaniel, B. T., & Radesky, J. S. (2018). Technoference: longitudinal associations between parent technology use, parenting stress, and child behavior problems. Pediatric Research, 84(2), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0052-6

Christakis, D.A., & Hale, L. (Eds.). (In press). Handbook of Children and Screens, Digital Media, Development and Well-being from Birth through Adolescence. Springer.

McDaniel, B.T., Uva ,S., Pater, J., Cornet, V., Drouin, M., & Radesky, J. (2024). Daily smartphone use predicts parent depressive symptoms, but parents’ perceptions of responsiveness to their child moderate this effect. Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 2. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1421717

McDaniel, B.T., Rasmussen, S., Reining, L., Culp, L., & Deverell, K. (2023) Pilot Study of a Screen-Free Week: Exploration of Changes in Parent and Child Screen Time, Parent Well-Being and Attitudes, and Parent-Child Relationship Quality. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5545779

McDaniel, B. T., & Summerhays Walker, J. (2024). Coparenting of child media use and associations with child media limits and frequency of media use in the United States. Journal of Children and Media, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2024.2402270

[Kris Perry]: Hello and welcome to the Screen Deep podcast, where we go on deep dives with experts in the field to decode young brains and behavior in a digital world. I’m Kris Perry, Executive Director of Children and Screens and the host of Screen Deep. Today, we’re going to talk about family life and how parents’ screen use affects their relationships with their children as well as children’s health and behavior. Joining us for this important topic is Dr. Brandon McDaniel, a senior research scientist at Parkview Miro Center for Research and Innovation. Brandon is a leading researcher looking into technology use and family life. In 2012, he invented the word “technoference,” to describe the interruptions in personal communication caused by attention to technology devices. I’m sure everyone listening to this podcast can understand what that means and has experienced it themselves. Let’s dig in to find out more. Welcome, Brandon.

[Brandon McDaniel]: Yeah, thanks. Glad to be here.

[Kris Perry]: I find it amazing that you came up with the word “technoference” just 12 years ago. The effects of smartphone use and digital technology in our lives is so profound, and yet we’re still grasping for the right words to talk about how it’s affecting us and our children. Can you tell us about how you came to be interested in what eventually would be called technoference and ultimately made it the focus of your research?

[Brandon McDaniel]: Yeah, honestly, back around 2012, when I was in graduate school at Penn State University, I was walking around campus. I would see everyone so engrossed in their devices as they were walking around, going across crosswalks, you know, sometimes talking to each other, other times not. I had young children. I would see it at the playground. I just saw it everywhere. I just noticed that our devices were beginning to become a really important part of our lives, and smartphones, especially, were something that was really engrossed in every aspect of our lives, or at least they were becoming that way. And I just wondered what that might mean for all of us. And that’s where I started diving in to see if – if that had any meaning. And not just that it would maybe have potential bad effects or any of that, or that the device itself would do that, but really even just thinking about the everyday things that come along with device use. If there was a beep or a notification or the fact that it was with them or any of these things? Does that have meaning? And, so that’s where we started to come up with this. Well back in 2012, I coined that term of “technoference”, technology and interference, just those two words put together. And it’s really getting at the idea that there’s everyday kinds of intrusions or interruptions that could happen that are due to technology use during our face-to-face time with one another.

[Kris Perry]: When I joined the Institute, I hadn’t heard the term technoference, and there was another term I hadn’t heard that people use to describe distracted media behaviors, which is phubbing, P-H-U-B-B-I-N-G. Can you explain the term phubbing to our listeners and how it’s different from the term technoference?

[Brandon McDaniel]: Yeah, the terms, at least in terms of the published research literature, kind of came out at very similar times. But phubbing is the words phone and snubbing put together. And, so really what we have here, the way I tend to view it, is that you have technoference, which looks at all different kinds of technology devices and the way that those things might produce interruptions, or distractions, or intrusions in our everyday sort of face-to-face time and interactions. And then you have this idea that phone use is a specific form of technoference where it’s specifically phones. And I’d say, in a lot of ways, it’s one of the most common forms of technoference that’s happening now, now that we have our smartphones with us all the time.

[Kris Perry]: So, at a very high level, can you describe how parent technoference and phubbing affect children as well as their other relationships in general? And what have you learned in your research about those?

[Brandon McDaniel]: Yeah, that’s a large question because there’s so much that we’ve actually done across these last 12 years. And it’s been really exciting to see this area explode in the literature, too, of people trying to figure this out along with myself. But really, I’ll say this. We’re finding that technoference is a really common experience, and like parent device-use during the time around their children is common. This is an example. In a recent NIH-funded study that I did, that myself and my team did, we found that parents of infants spent 27 % of their time around their infant also on their smartphone. And that was objectively measured and tracked. So that’s not just a self-report, which often can be biased, and it’s hard to remember our phone-use, all that. So that was quite interesting. So, it is pretty common. And there are a lot of reasons we find that people will use their device, such as being able to regulate their emotions, or cope with stress, or out of boredom, to obtain support. There’s many, many different reasons. And– but in terms of what this looks like and what this might mean, if they’re doing it a lot around their children, their children might begin to react to that, to this technoference, to this parent device-use with increased behavior problems or negative emotions or those sorts of things over time, especially young children and infants, and teens we can talk about another time too. But for parents specifically in all this, we also see some negative effects where they might, their responsiveness to their child might begin to get impacted a bit in terms of the speed of that response, the contingency, the warmth of the response, as well as their perceptions of if they’re in a two-parent sort of, or two-caregiver sort of household, they might perceive their partner in parenting, their co-parent, a little differently and more negatively if there’s a lot of this technoference going on. They might even get some depressive symptoms that develop over time from their use. I’ll just say this: it’s really complex, actually, when we dive in. There are both good things, support, and also a lot of ways that it can hinder interactions and, sadly, even the ways that it gets used to support someone, they may also end up feeling guilty, or it may not be the most effective way that they could have done something with their device or used the device at that time. I just want to say this: It’s – In understanding this, we need to really comprehend that it is– it’s complex. We can’t go at it from this frame that it’s only going to have negative effects on everything. And that’s just like a complex mess of both feelings, impacts, and everything over time. So it really depends on when, why, how, and the context of the use.

[Kris Perry ]: I appreciate that point about complexity and the multiple number of variables that are impacting parents and their device use and the feelings that may come up for themselves and with each other. Can you tell us anything about children’s perceptions of their relationships with their parents? Is there research being conducted about the way children are being impacted, their feelings, their reactions to their parents’ device use?

[Brandon McDaniel]: Yeah, yeah. So, in some of my own research, I mean, this was parent-reported, so we’ll say that first, but in some of the research that we’ve done that was parent-reported, we saw increases in child behavior problems over time if there was technoference that was happening. So, we even saw a bit of a cycle in our kind of longitudinal research study. We saw that as parents engage in more of their device use and technoference, that the child might react with more behavior problems over time, and that that might then lead to greater stress on the parent which might then lead to more technoference, and you end up in this cycle. As well as, if we look at infants, we’ll see, like, negative emotional reactions, like negative affect, crying, or bids for the parent’s attention. If we get into teens, we actually can see–now, they are able to express a bit more of what they’re feeling. So if you look at them, you’ll hear words like, it makes them feel upset or frustrated, mad, angry, like they’re not worth as much as the device, maybe in those moments to the parent, which really kind of sad to hear, but this idea that teens may actually begin to react in ways to where they disengage with [into] their own devices more and develop problematic habits on their own devices and a lot of other things. So we could go on and on. So I’d love to hear if there are other things you’d like to know about that.

[Kris Perry]: There are because we know how much what we do versus what we say impacts our children while we’re actively parenting them, and you’ve mentioned the how, when, why, what, and how much those things matter. What major contextual factors should parents think about when it comes to their media use in front of their children?

[Brandon McDaniel]: I think here, one way to think about this is that you want to think about the message that you’re sending to your child. So if they’re an infant, or if you have a young child or an infant, they rely very heavily upon you for their, you know, daily well-being, for their development over time, and you’re their entire world. So to you, you may view it as, “well I’m just, you know, they’re not really doing anything. They’re not really noticing.” But I guess we’re finding that they really are noticing that you’re on your device. And if you’re doing that a lot, then it could have potential negative effects on them. Because at a young age, they need your eye contact, and your attention, and your involvement to be able to–even help them to regulate their own emotions over time and to learn how to regulate their emotions so that they can be set up better developmentally for their own life over time. If we look at older children or teens, for them, I think, it’s a lot more of communicating what it is that you’re doing, and when and why, and thinking carefully about that, and making sure that you’re helping them understand and realize they’re still the most important thing to you. And – so there may be times that you need to do it, but you should assess whether that is something that you need to be doing during that moment. Because really, I’d say for most of us as parents, we want to be a good parent. We want our children to know that we love them. And so it’s really important to understand that the more our devices come into our space and time around our children, there’s the potential for a growing divide to happen, even unintentionally, where you begin to drift apart or to not have as strong of a connection because the device use presents a bit of a barrier. Yes, there’s ways that you can use it together, and that can be fun. But if you’re getting on your device during time that you’re around your child, and it’s happening quite often, then those are times when eye contact is getting broken, the synchrony of the interactions, the conversations back and forth often will be impacted. And if we look at even just adults, we can see differences in how adults and others will perceive the person that they’re talking to or interacting with, as it just kind of degrades the quality of everything. And that’s not really what you want to happen. So it’s okay when it’s happening sometimes, but we have to be careful.

[Kris Perry]: Absolutely. And listeners, you can learn more about technoference and its impact on children in the chapter Brandon McDaniel authored on this topic in the forthcoming Handbook of Children and Screens, Digital Media, Development and Well-being from Birth through Adolescence. This topic is making me a little anxious because, as a parent, I have experienced both the guilt and the worry of using a device in front of my children and knowing that it was interrupting my connection to them, as well as recognizing as they got older that they were doing the very same thing at the dinner table or when we would have family over. And I would feel both frustrated with them and a little bit angry at myself for letting this whole thing unfold the way it had. And it was so iterative and incremental. It didn’t seem when I started, it would ultimately result in such a mirror image of my behavior, but it certainly did in a very short period of time. And I imagine many listeners are experiencing this same phenomenon in their own homes. One of the findings I’ve seen in recent years that I find also fascinating and troubling is that it’s not just parents actively using their phones in front of their children, like phubbing, but the mere presence of a phone at all, not even being used, that can have impacts on personal communication and relationships. Can you tell us more about that?

[Brandon McDaniel]: Yeah, so not all studies that are out there show these effects of just the mere presence, but some of them are showing effects, negative effects on interactions, even if the phone is just there on the table or something like that. And some of the reasons that might be happening at times is because we’ve really formed –many of us have formed a very strong attachment and kind of cognitive awareness of our device at all times. If you think about it, it goes with us everywhere we go. We use it for many different aspects of our lives, so it’s no wonder that it’s so integrated into everything that we do. But that can make it to where our thoughts may dwell on the device, or our attention may get turned back to the device, even when the device isn’t necessarily doing anything, and we’re not actively using the device. Also, our partner in the interaction, or the child, may have their desires or expectations for that interaction. Maybe they wanted undivided attention at that moment, and they see you sometimes glancing at the device. Or maybe they have a negative view or perception of the device itself because of some of the ways that it has impacted interactions in the past or been used by you. So, if you think about all the connections between those things, they could even– they could end up with those lower-quality perceptions of how this interaction and time together is going. And it could also impact the synchrony and the quality of the interaction, depending upon that cognitive and emotional load you might be carrying from just the device and how it’s connected to you.

[Kris Perry]: Is it– Is it anything like the Pavlovian response? Just the sight of this object starts a domino effect in the brain that mimics the same impact that would happen if you were to pick up the phone and start to use it. Just the sight of it triggers this response?

[Brandon McDaniel]: I think for some people, that, that it’d be a hypothesis, but I’d say for some people I think it could get to that point, especially if this is something that’s been having a negative effect on their interactions or relationships over time before this point. Yes, they’re going to view that device negatively.

[Kris Perry]: You’ve talked a little bit about infants and teens and their response to technoference. Is there anything else we should know technoference effects in children based on different ages?

[Brandon McDaniel]: I’d say there really are a lot of similarities in terms of the effects or the fact that there are the potential for these negative kinds of effects. It’s just that they manifest in different ways because they’re developmentally different. So, you know, infants might show those negative effects by the way that they cry or bid for the attention. Whereas young children might show that with increased behavior problems, which might go a couple of different directions, they might act out sort of these externalizing kinds of behaviors, or for some, they may begin to show an internally– internalizing kind of behaviors like withdrawal from interactions. Whereas when you get into teens, they might be showing things like increased depressed mood or questions about their own self-worth, increased problematic use of their technology, cyberbullying behaviors perhaps, or other kinds of risky sorts of behaviors. Essentially, it’s like acting out of a child, but now they’re at a much higher developmental level. So it’s important for all ages. I often study what’s happening in infancy, because they’re completely reliant on their parent or caregiver for their care and development for some of the reasons that we already talked about in this. So, that can really impact them a lot if, and their whole developmental trajectory over time, depending upon how much the device is being used, the ways it’s being used, and if it’s interfering with the parent’s own parent responsiveness and caregiving that the child is receiving. And honestly, that’s one of the things I think a lot of us are beginning to or hoping to figure out over time, is the longitudinal sort of downstream effects of what’s going on here. If it’s happening to them a lot in infancy and early childhood, what is that going to mean for when they are a teenager, for example, or a young adult, or even a parent themselves?

[Kris Perry]: I know that at the Institute and from talking to many people, we’re all really interested in whether or not infants can even recognize if their parents are distracted on phones. And I should mention that you’re the principal investigator on the Infants and Screens Research Grant that we awarded at Children and Screens, where you’re exploring the impacts of parental phone use on social-emotional development and early infancy. Can you tell us a little bit about that project?

[Brandon McDaniel]: Yeah, yeah. So we’re really excited about that one. We’re right in the middle of data collection and everything for that. So we’re looking at over 150 mothers of young infants, looking at them across infant age of two months, three months, four months, and five months. And we’re diving in and having them complete what we call EMA, or ecological momentary assessment surveys, five times a day for five days. So there are these brief surveys. And so these bursts, we could say of surveys at two months, three months, four months, and five months, where what we’re really trying to understand is a bit of the empowerment that can come, potentially, from a mother’s smartphone use—again, going back to this idea that there can be support and good things as well, potential positives. So maybe they’re feeling really supported by the use. Maybe it helped them to cope in that moment. Maybe they got exactly what they needed so that they could re-engage with their infant the next moment. So understanding this in this moment-to-moment basis, as well as – maybe it didn’t go so well, maybe what they were doing interfered with the way they were feeling, how connected they were to their baby or the guilt that they experienced or all these other kinds of negative phone use feelings that might come along with that too. So we’re trying to understand the complexities of all of that while also measuring, objectively, tracking, their phone use across this whole longitudinal period so that we can start to see from moment to moment what kinds of effects does phone use during the time that they’re around their child have on their own mental health, on their own responsiveness, as well as on the infant’s behavior and expressed emotions and affect over time. And so we’re looking at that moment to moment, but then also trying to think about all of these momentary processes that might be happening and the empowerment, and guilt, and negative use that might occur. And then does that have downstream effects? So, across those four months, do we see differences in the infant’s own emotional development from two months to five months based on things that are happening with mother’s smartphone use?

[Kris Perry]: Can you share any preliminary findings from the study or is it too early?

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: It’s a little early, but I will say that some of our preliminary work is showing things like the more depressed mothers of infants are, the more likely they are to engage in problematic mobile gaming sorts of behaviors, which to me is fascinating because really no one’s looked at the mobile gaming behaviors of parents and especially parents of infants specifically to see what that might mean and it’s not something we often think about, but there are many different aspects to smartphone use, so there’s one of them. These sorts of being drawn into greater mobile gaming use or having your thoughts dwelling on mobile gaming use, that sort of stuff. So it’s rare, but those that are depressed are more likely to end up falling into those sorts of habits. We’re definitely seeing that empowerment and feeling, as well as feelings of guilt and technoference and those things are definitely happening and commonly. What we don’t know yet, and what we’re going to start analyzing, is what does that all mean in terms of its connection as we think about how empowerment and negative phone use feelings might be connected to their own perceptions and infants’ behavior. We have seen, for example, that it looks like during moments when mothers feel like technoference has occurred, so they’re perceiving technoference, they also perceive themselves as less responsive in those moments, which isn’t surprising, but is interesting. We also see that, we are seeing some things to suggest, so we don’t know yet, just preliminary, but there may be differential sorts of effects moment-to-moment as opposed to day-to-day even, where one thing it looks like is during moments that they use their phone more around their child they might actually feel a little bit happier, like the mother might feel a little bit happier in that moment specifically, maybe it’s a little hit of dopamine or they felt like they got what they needed right then, I’m not sure exactly yet, but then on a daily basis, on days that they use their phone more around their child than on days when they didn’t, they actually feel less happy on those days. So it’s this interesting mix of where it’s like it may help maybe a little bit in the moment, but does it help the entire day? We don’t know. Is it gonna help longitudinally? We don’t know yet, so there’s a lot to figure out.

[Kris Perry]: It’s become almost reflexive behavior for many adults to reach for their phones as kind of a digital calming tool for themselves when they’re stressed with all the things that justifiably stress parents out these days. You just shared some preliminary findings from your own study, but what does the other research say about the role that levels of parental stress and parent mental health have on parent media use and its effects on kids?

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: So although parenting is rewarding or can be rewarding, it’s also inherently very stressful and difficult at times, I don’t think any of us would argue that point. So, all adults or people, just when people are stressed or depressed or down, often many people turn to device use, and we’ve found that parents are no different. The parents who are rating more stress, they’re feeling more depressed are also the people who are going to engage in greater device use. In some of our recent work where we objectively measured smartphone use, so this is another NIH study that I was in. When we objectively measured parents’ smartphone use, we found that they used their phone more around their child on days when they were also feeling more depressed. So it’s definitely connected, and I would say there’s enough research out there to show that it’s definitely something that is bidirectional, and we don’t really need to have this argument of which is causing which. It’s quite clear that the more people use their device and the ways that they use their device can lead to depressed mood or even greater experiences of stress, and that those that depressed mood and greater experience of stress can lead to device use and that can even become a cycle.

[Kris Perry]: I know you’re a parent yourself. How has your work informed how you and your family use media?

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: It’s definitely impacted it. I mean, I’m a lot more cognizant of how and when I use my devices during parenting or around my children. Just as an example, I tend to look for ways to leave my device or my phone in a different room or in a different space when I’m going to be around my family. Just because that, one thing I have found in my research with others, is that it’s very difficult for us to control our device use. Self-control is not enough. If you think about the way they’re designed, for children as well as for adults even, we’ve all got these supercomputers with us that have been designed by multi-billion dollar companies to draw us in, to keep us coming back, to keep us engaged, to bring our attention back to those and our thoughts about those devices and what’s happening on those devices, and it’s really a losing battle. Eventually it’s gonna get you. That’s one way to think about it. So setting up barriers for yourself to give yourself some time to make a cognizant, like intentional decision is really important. So I give myself space, where to get on my device, I’d have to walk five feet, for example, during family time, because that often is enough of a time or enough space to be able to make an intentional decision as opposed to just picking it up because it was laying there. And I try to set a good example for my family and my children so that they know how devices should be used during time together, the kinds of eye contact we should make when someone’s talking to us, just giving them those things that we would really want in a relationship and in interactions with others. We’d want to feel valued, we’d want to see their eyes, right? That’s just really important.

[Kris Perry]: It’s pretty interesting that one of the top researchers on this topic of technoference and phubbing is struggling himself with keeping the device away during important parental moments and I think that’s an important point for our listeners is that this is, it isn’t just you, it’s all of us, we’re struggling with this balance of our digital lives and our real lives, and I really wanna call that out because I really appreciate your honesty in that answer. I also saw a study of yours from last year in 2023 that piloted a screen-free week for parents and children. Did you learn anything different from that?

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: So what’s interesting with that one is, just to explain it, we didn’t make people go screen free for the entire week. We took it more as, well, this is a screen-free week, but what we’re really asking you to do is just engage in some screen-free times each day with maybe some more developmentally-appropriate activities cause these were with a – it was this very small pilot kind of study, 24 parents or caregivers of a preschool-aged child and had them do that and then we assessed them a week after that and then four weeks after that. What I believed is that it might be possible for us to, as they engaged in some of these screen-free times, they might end up having some better quality interactions during those times or having a more rewarding experience or even just feeling a little bit more satisfied with their relationship with their child. Ultimately, what we found was that only looking at that for a week, it’s not going to have huge effects because they only did it a little bit and they only did it sometimes. But, we did see actually some interesting effects coming out of that where parents became – it seemed like people became more aware of their own tech habits and so they began to cut back on their own device use around their child and they actually ended up feeling less depressed over time. So, I think the way that we use our devices often are connected to us in a variety of ways that we don’t expect, such that when I think as parents, we are very invested in being a good parent and we often feel guilty about the ways that we use our devices or don’t use our devices during times around our child, and if we begin to set up some tech-free times or zones around that, which honestly I’ll say is one of the easiest things for a person to do, one of the easiest ways to control your tech use is to set up a specific screen-free or tech-free time where you’re like, “that’s the spot where I won’t do it,” and then when you begin to do that, let’s say you gain a bit more efficacy around those things, you feel a little bit better, less guilty, and there’s some more rewarding interactions that can take place, and it looks like that’s what happened for these families too.

[Kris Perry]: You just talked about parental guilt about media use and we hear from so many parents that they don’t know what the right thing to do is with their children in screen use but the reality is almost, or most adults don’t know what the right thing to do is with their own media use.

What do you think is the single most important piece of advice you would want to give parents today, based on your work, that would help children have healthier lives and outcomes.

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: So obviously I’m gonna go and talk about parents because that’s one of the things that we often don’t think about is ourselves and our own use, we’re often thinking about our child’s use. Now that’s a whole different bucket and very important to think about, but for ourselves, I’d say we need to look at the ways that we can be more present, that we can consider whether our use and what we’re doing is actually what we wanted and what we needed for us. So, for example, we often find that people fall into use in ways that they didn’t mean to, or they thought would make them feel better, and it may not actually be doing that. So, understand that we live in a technological world, it’s a problem that we’re all dealing with, it’s okay that you fall into use here and there, that maybe you even struggle with some self-control with it, that is so common. That’s the first thing we just need to understand. Just don’t let it become the norm in your life and with your children and your family, where you slowly, even unintentionally drift apart because you allow phone use or smartphone use or device use to fill more and more of that time as opposed to having yourself be more focused on your family and your time. So again, one of the easiest things that you can do, I would say, if you’re trying to get started, is to try to set up some screen free times or some screen free zones in your home. Maybe you might decide for yourself that you’re not going to take your phone ever into a child’s bedroom, because why would you need it there? Maybe that’s a space where you would only interact with the child and you don’t want any distractions. Or maybe it might be mealtime that’s the easiest for you and your family to have no screens and interact, completely be fully present. So it can look a little different for every family, but trying to focus on ways to be a bit more present.

[Kris Perry]: Where is the research going on this topic and what do you think is the next important thing to study or the aspect of parent media use that needs to be studied better in order to better help families and children thrive?

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: Honestly, it’s some of the things that we’re trying to do, and I think many people are trying to do now, is to get a better grasp and handle on the complexities of what’s really going on here. Because parents feel supported by, while also simultaneously guilty for using their phone around their child, for example. And there are so many positive or potential positive impacts of that device use for – you could imagine a parent who in that moment is so stressed out that she’s about to lose it with her baby even, you know, and she turns to device use in that moment that helps her calm down and she’s then able to re-engage with her child and so the yelling or the negative interaction or whatever didn’t happen in that moment so that was a good thing, but simultaneously she maybe feels guilty for doing it so then what does that mean for her and her mental health and parenting responsiveness and other things over time? But at the same time, we can’t also ignore that the fact that they disengaged into their device, the child’s still going to see that as a distraction and a disengagement, so the child will also have their own kind of unique experience of that. So trying to understand the multiple unique experiences that are happening while also understanding that there’s both support and hindrance or kind of like empowerment and these negative types of things and feelings that are happening simultaneously, and what do those mean? Is it going to mean that all this stuff that we’re looking at ends up sort of having a more null kind of effect or like not much of an effect longitudinally over time? Or is it going to be that one of these weighs out more than the other? Is it going to mean that it has a certain kind of effect, like it’s more of a null kind of effect for parents and their perceptions, but it’s a stronger effect for babies or young children because of what they perceive or see or feel? It’s really hard to know. So really getting out into the research to understand the simultaneous sort of positive and negative effects and differential kinds of effects that can come depending upon how, when, why, and how the device is being used, as opposed to only measuring that device use happened or that technoference or phubbing happened or was experienced.

[Kris Perry]: But haven’t we been studying the impact of parental mental health, for example, postpartum depression on infant development, and haven’t we also been studying parental reactions to infants and young children depending on how they present emotionally, for decades. And when you add in a new phenomenon, such as technoference or phubbing, to a larger body of knowledge around parental-infant attachment, dyadic attachment, does that inform – can you extrapolate from earlier studies on attachment as you uncover what’s happening now with technology interruption?

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: I mean I think one of the things that we can extrapolate is that if device use is causing distractions to be very, very frequent to where it’s impacting all of the different aspects of parenting sensitivity, like the contingency of the response to the child, the appropriateness of the response and so forth, then that might have long-term effects on attachment and emotion development and these sorts of things. I think what we just don’t know yet is whether that’s actually going to be the case because of all of the different complexities and intricacies that I just mentioned. That, although it might impact the responsiveness of the parent, at the same time, in the very next moment, it may have actually increased and improved the responsiveness of the parent, and although the child was feeling a bit ignored in the moment prior, now all of a sudden they’re having this really positive experience because of what the parent gained from what they did on their device a moment before. So it’s too difficult to say at this moment what it will mean long-term or developmentally.

[Kris Perry]: It just reminds me of the advisory from the Surgeon General and so many others that since we are still learning about the impacts, take a caution-first approach to your use and find ways to buffer your relationship with your children until we do understand this better. You mentioned earlier co-parenting use and screen use and parents don’t always agree on media use rules for themselves and their children. Does your research indicate anything about specific considerations for co-parenting, parental conflict around media use, and media practices in households where parents aren’t necessarily on the same page?

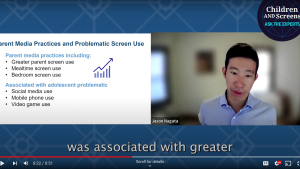

[Dr. Brandon McDaniel]: So some of the work that we’ve done has looked at ratings of co-parenting and child media use. So how much they’re supporting one another or feeling like they’re undermining one another or having conflict about their child’s media use. And what we see is that if – the better co-parenting that’s happening, the less that the child is going to engage in media use, the more consistent rules are, and all of that. So essentially what we’re saying here is that the way that parents manage media use together is definitely going to have effects on the ways that children use media. And so it’s really, what it becomes is it’s important for parents to find ways to be on the same page and whether they need to be doing this away from the child first so they can discuss and get on the same page to then be able to support one another in those moments when children push back or when there’s a particular rule that maybe the other parent would have been a little more lax with, it becomes really important. If you have two kind of competing views of what should be happening with child media use, it can also lead to a lot of problems over time.

[Kris Perry]: Thank you so much, Brandon, for this insightful discussion and your impactful work helping us understand how digital behavior is shaping lives, especially for children and families. And thank you to our listeners for tuning in.

For more information about Brandon or a transcript of this episode, visit ChildrenandScreens.org where you’ll find a wealth of resources on parenting, child development, and healthy digital use. Until next time, keep exploring and learning with us.