Increased rates of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents have coincided with a continued rise in average daily hours of youth digital media use. What do parents and educators need to know about media use and youth suffering from anxiety and depression? What are helpful strategies to talk with vulnerable kids about their media use and help them build self-monitoring skills? What types of media are more likely to exacerbate mental health issues, and which might offer therapeutic benefits?

On This Page

Recognize Problematic Anxiety

“It’s normal for any parent to have anxiety and any kid to have anxiety,” says Erin Berman, PhD, Clinical Psychologist at the National Institute of Mental Health. Children may feel anxiety as a momentary, normal response at the beginning of a school year, after reading traumatic news or when experiencing stressful one-time social situations on- or offline.

When does anxiety cross into being problematic to teens? Berman suggests looking for the following signs of more serious distress from anxiety:

- Persistent (more than a few months) and intense feelings of anxiousness that interfere with normal functioning

- Irritability

- Sleep issues

- Problems being alone

- Not liking to be center of attention/social anxiety

- Sudden school absences

- Disinterest in making friends

- Confining themselves to a bedroom most of the time

- Fight or flight symptoms such as: Stomachaches, headaches, nausea, frequent trips to bathroom, tightness and pain in chest, dizziness, sweating, heart racing

Recognize Warning Signs Of Depression

Teens suffering from depression share some similarities to problematic anxiety and include sustained and persistent symptoms that may include:

- Sadness

- Disengagement from normal life activities previously enjoyed – school, activities, friends

- Self-injury

(Janis Whitlock, PhD, Scientist Emerita, Cornell University; Founder and Director, Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery)

Understand That Context Matters With Digital Media And Mental Health

“We know that there are many ways that we might see depression being associated with digital media use, including the ways in which mood might affect what teens choose to do online, what time they go online, what platforms they might engage in,” says Mitch Prinstein, PhD, ABPP, Chief Science Officer of the American Psychological Association.

“The research in this area is continuing to suggest that there’s a combination of who a child is that interacts with what specific kinds of digital media activities and platforms they engage in that might be most important to understand any particular outcome. A resilient adolescent who uses digital media to chat with their friends and talk about the news might be fine. However, someone that’s experiencing social or psychological vulnerabilities and engages with the most harmful or addictive or concerning stimuli on digital media might have a much worse outcome,” explains Prinstein.

Look Beyond “Active” Versus “Passive” Use

Much advice for healthy media use focuses on the positive aspects of “active” or interactive use over more negative outcomes from “passive” media consumption. However, Sarah Myruski, PhD, Assistant Research Professor in Psychology, Associate Lab Director, Emotion Development Lab at Pennsylvania State University cautions against this limited view. “We’re finding that not all active forms are beneficial,” she says. Going deeper into which types of use have positive or harmful effects on a specific child is recommended.

For example, Myruski notes that active usage for socializing that comes at the cost of excluding face-to-face interaction wouldn’t necessarily be a positive net use of digital media. Conversely, there are some passive forms of tech use like receiving information, news, or entertainment that are not harmful, compared to passive use like “doom scrolling” through endless social media feeds.

For youth suffering from depression, passive social media use like listening to music and watching videos is common as a form of temporary distraction or escape in order to cope with distress or self-harm urges, says Lizzy Winstone, PhD, at Population Health Sciences, University of Bristol, UK. Yet some depressed teens who actively are help-seeking by messaging or posting online can sometimes be viewed by peers as attention-seeking and risk being bullied or ostracized as a result.

For youth of color, Henry Willis, PhD, Assistant Professor, Clinical Psychology Program, Director of the Cultural Resilience, Equity, and Technology (CREATE) Lab at the University of Maryland, College Park notes the double-edged nature of some active screen time. “We know that [youth] may actively engage others on social media around race-related topics as a way to resist or engage in activism. That can be good in terms of helping them cope with some of those experiences. At the same time, we know that also opens them up for attack from trolls and other people, so it can be tricky,” he says. Passive use of TikTok to watch videos that promote joy or resourcefulness can also benefit youth, he notes.

Educate On The Most Harmful Uses Of Media

“Parents need to know about doom scrolling,” says Berman, so that they can help their children understand how harmful that activity can be when suffering from anxiety or depression. Doom scrolling can be defined as persistently attending to negative information in news feeds about crises, disasters, and tragedies.1 “When you’re depressed or down or anxious, I can’t tell you how many patients just fall into the doom scrolling trap. Knowing the difference [between normal and doom scrolling] is more helpful than just saying, ‘Don’t scroll!”’ – because everyone scrolls.”

Algorithm-driven social media feeds can sometimes provide more and more extreme and harsh content as a way of keeping people engaged, says Anne Maheux, PhD, Assistant Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Winston Family Distinguished Fellow at the Winston National Center on Technology Use, Brain, and Psychological Development. “This is different from cyberbullying,” she notes. “This is exposure to hate, exposure to violence, and exposure to potentially traumatizing content.”

Role Model Healthy Use

Looking at your own screen use and role modeling appropriate media use is very important, says Sandra Fritsch, MD, Medical Director, Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. “I go out into my waiting room and see no one talking anymore. Everyone is on their separate screen.” Participating as a family in screen-free time where the whole family commits to taking a walk together and meals are uninterrupted reinforces a healthy balanced approach to using digital media. “Be able to look at your own use, make some modifications, and then go forward with that,” Fritsch suggests.

“I’ve had little kids in my office tell me they’d rather ride with their grandparents because their parents are busy texting and they feel safer riding with their grandparents,” says Fritsch. “What are we doing if we say ‘Don’t be on screens’ and we’re checking our own screens? We can model it behaviorally and the kids see that,” adds Berman.

Encourage Meaningful Social Relationships

“We know from extensive research that social interaction, adaptive social behaviors and the opportunity to have meaningful, emotionally-disclosing relationships with others are important protective factors against depression, particularly in the context of stress,” says Prinstein.

While digital media is often an important way for teens to feel socially connected, anxious teens who habitually prefer media use to face-to-face interactions “might miss out on opportunities to hone their social skills, to get practice managing their emotions and real time interactions,” notes Myruski. This in turn may intensify the desire to stay in the more controlled online environment.

“Science tells us that one of the biggest predictors of depression or worsening of depression for those already experiencing symptoms is social isolation,” says Prinstein. “One of the best treatments for depression is what we call behavioral activation or, in simpler terms, getting kids out of their rooms or homes and actual face-to-face engagement and exercise.”

Prioritize Media Interactions Most Like In-Person Ones

While an overall balance between digital media use and face-to-face time is important for healthy social functioning, when using digital media or when in situations where in-person interactions are not possible, it’s best to opt for forms of digital communication that include some real-time social cues, like voice calls or Facetime, because they more closely resemble in-person interactions, says Myruski.

Teach Self-Monitoring Skills

Youth (and adults) have enormous demands placed on their attention by social media platforms designed to keep them scrolling. “Many young people, but especially those with mental health difficulties, can struggle to self-regulate their social media use, sometimes describing themselves as feeling ‘addicted’,” says Winstone.

Monitoring how one feels before and after media use with something like a mood tracker can help with anxiety, adds Myruski. “There’s evidence that simply self-monitoring our digital media use without even cutting back or trying to change anything else can help ease anxiety.”

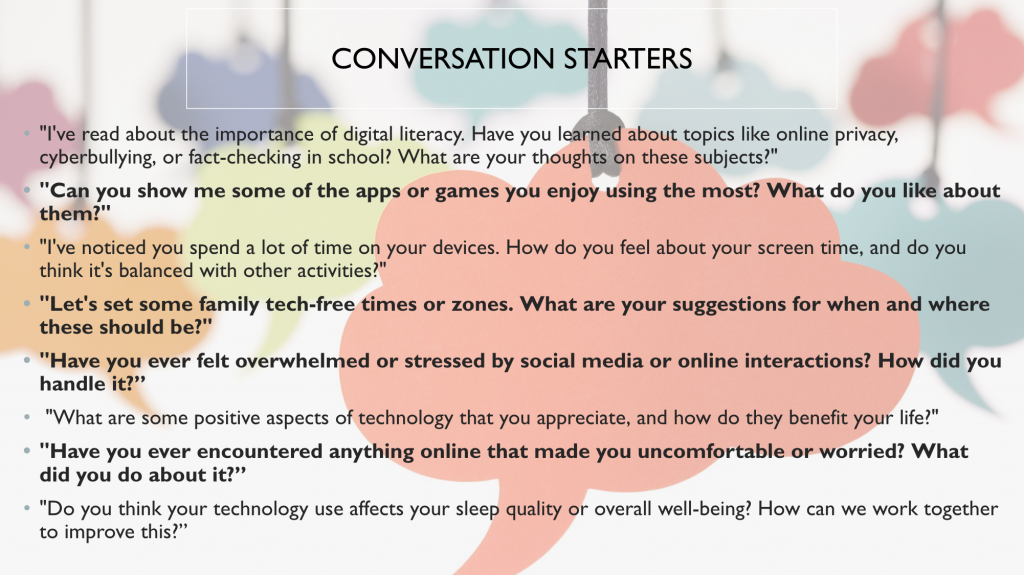

Help teach your teen to self-monitor if they will allow it, encourages Myruski. “Browse the social media feed together. Ask them what’s drawing their attention, what are they thinking and feeling when they see this different content? And also ask them to talk about what they experience online in their day-to-day life. What’s fun about it? What’s worrying about it? What do they wish was different?”

“Young people are just going to need to be more self-aware than they’ve ever needed to be at a young age,” says Whitlock. “They have to navigate social media environments that require them to know a lot more about themselves and recognize early warning signs that they’re getting overwhelmed by stimuli.”

Avoid Over-Restriction Of Digital Media

“While some boundaries are important with digital media use, high levels of restriction could lead teens to hiding their use, like going to the bathroom during ‘no screentime dinner’” says Myruski. In addition, a highly restrictive approach to media use may increase teen stress and anxiety because of the social consequences of not being a reliable or supportive friend to others.

“Taking away devices or disallowing the connection that happens online as a punishment does not help promote a lot of responsibility or help youth learn how to manage with targeted intervention,” notes Whitlock.

Communicate Concern With Calmness And Validation

Many parents concerned about digital media use that may be contributing to symptoms of anxiety or depression do not know how to approach their child with their worries. “Kids and teens want the parent to be interested and validating, and to stay calm,” says Sandra Whitehouse, PhD, Senior Director and Senior Psychologist of the Anxiety Disorders Center at the Child Mind Institute. “An easy manner seems to really help.”

“Treat teens as experts in this and let them lead the conversation,” says Willis. “They may know a better roundabout to curb their use than you do.”

For those with children already in therapy, Whitlock suggests consulting with the therapist may help identify strategic ways to have fruitful conversations.

Use Questions And Be Collaborative

Fritsch suggests engaging with curiosity rather than talking “at” teens, asking questions like “‘Are you worried? Do you have any concerns about your own use of screen time? What do you think is the healthy part? Where are the worrisome parts?”

Working together in collaboration also may help reduce teen anxiety around parental conversations, as they will feel they have some control instead of just being told what to do, says Berman.

One way to lead into a collaborative conversation about media use Whitehouse suggests is to ask for their feedback on your own screen use, and what guidelines they think would be appropriate for your use.

Be Open To Dialogue However It Shows Up

Digital devices may provide avenues of parental support and communication for youth having difficulty sharing emotions or vulnerable thoughts in person, says Whitlock. For her daughter, she found that “there were things she could say in text that she would not tell me at the moment as a 16-year-old,” so they developed an emoji-based text check-in that helped her keep tabs on her daughter’s immediate emotional state without being overwhelming.

Know The Risks – Media And Self-Harm/Suicide

Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for 10–14-year-olds and the third leading cause for 15–24-year-olds, says Vicki Harrison, MSW, Program Director of the Center for Youth Mental Health and Wellbeing, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine. “Almost a quarter of high school students reported seriously considering suicide in the past year.”

While some young people who self-harm find viewing self-harm imagery helpful in managing their urges, for others this can lead to exposure to content where they can learn about new methods of self-harm and run the risk of being inadvertently exposed to triggering or increasingly extreme material, explains Winstone. In addition, viewing images of self-harm can lead youth to compare their own self-harm with others, sometimes leading to feelings of competition for more severe injury and supporting development of a “self-harm identity,” she says.

Parasocial attachment to certain celebrities or media personalities may exacerbate “social contagion” risk to vulnerable youth if those personalities engage in suicide or self-harm behavior and are subject to media coverage of it, says Harrison. “The greater the media coverage and/or the closer they are to the individual whose behavior they’re observing, the more intense the exposure to that, the more the effect. They may be identifying with an individual, especially if it’s a celebrity or someone very well-known.”

Media or social media coverage that exacerbates “social contagion” of suicide content include sensational headlines, descriptions of specific methods used to die by suicide, and pictures of detailed descriptions of the deceased individual. If individuals choose to share or post online about a suicide, they can avoid amplifying and adding to the effect on young and vulnerable people, says Harrison. “You don’t want to include details, you don’t want to sensationalize, and you don’t want to speculate as to reasons behind a death.”

Understand Interplay Of Emotion Regulation And Anxiety With Media Use

“We know from decades of research that difficulties with emotion regulation underlie elevated anxiety in youth, and emotion regulation capacity in the brain undergoes profound development during adolescence,” says Myruski.

Teens with emotion regulation and anxiety problems may gravitate to digital media rather than face-to-face social interactions because of the heightened ability to control the digital environment, explains Myruski. “That could be likely because online platforms offer greater controllability. We can plan out what we want to say. We have time to consider how we’re going to respond and also curate how we present ourselves. People with emotion regulation difficulties, and or anxiety, especially perhaps social anxiety, might find those features of digital media particularly appealing.”

Myruski cites recent research indicating that difficulties with emotion regulation might put some teens more at risk for the downsides of digital media use. Their strong preference for using digital media might represent a heightened need for control and avoidance of unpredictable and emotionally taxing interactions that occur face to face.

Work To Reduce Overinvestment In Social Media Metrics

“A lot of teens are invested in the number of likes or quantifiable metrics of peer approval that they receive online,” says Maheux. “I’ve heard directly from teens that they engage in all sorts of behaviors to try to get more likes,” and will sometimes delete content quickly that doesn’t get the positive feedback they crave. This intense investment in social metrics is not a good substitute for quality friendships and peer relationships. “If teens have opportunities to think critically about their motivation for posting things and seeking out this kind of online status, that could help them engage in more beneficial ways,” she suggests.

Youth suffering from depression may suffer from the inherent pressure on social platforms to present a “happy” or confident self-presentation in content posted online, which can feel draining. In addition, “when posts don’t receive positive feedback, young people with depression may also be more likely to internalize this, which can then further exacerbate those negative emotions or poor self-esteem,” says Winstone.

What To Do (And Not To Do) During A Child Anxiety Attack

If your child or student is experiencing an intense anxiety attack related to something on their phone or online, it can be difficult to know what to do to help them through it. Berman suggests a few key approaches to successfully assist.

What to Do:

-

- Listen and don’t talk a lot. Kids are not able to listen when they are upset.

- Model being calm. This can be hard as a concerned parent. If you can’t do it, find another person or even a pet in the house that can help bring calm.

- Remind them that the anxiety or panic attack always ends.

- Grounding – use mental or physical grounding techniques to distract and calm the senses.

- Slow things down and focus on problem-solving.

- Say helpful things like “Take your time” and “It’s okay” or “How can I help?”

- Do not say minimizing, unhelpful comments like “Quit being dramatic,” “Toughen up,” “Try harder,” “You’re being lazy,” or “You’re crazy”.

Practice Emotion Regulation And Coping Skills

To help a child cope with anxiety from both online and offline situations, parents should avoid over-accommodating and instead help them practice the skills they need to cope with situations that give them anxiety, says Berman. “As a parent, being too directive or too reassuring can be problematic,” she notes. “What anxious kids need to know – and you need to encourage – is that they’re brave, resourceful, and are thinkers.”

For example, Berman suggests that when a child is experiencing a high-anxiety time or is scared to text a certain friend, coach them by saying “Don’t let your mind tell you you can’t do hard things – because you absolutely can.” For a child that prefers only online interactions and has social anxiety, Berman suggests role-playing or helping them find virtual reality exercises that allow them to develop situational social skills.

If listening to a parent isn’t working, finding a peer-aged relative or friend who can help them practice may be more effective. “Young people tend to be more likely to absorb the information if it’s shared by peers,” says Winstone.

“Seek ways to practice emotion regulation throughout everyday activities,” says Myruski. “Talking through emotions with things like journaling, artistic expression, and/or through interventions that are specifically designed to improve emotion regulation like therapy and mindfulness practices,” can help improve emotion regulation which can help prevent anxiety.

Foster Media Literacy For Resilience

“There is some evidence that media literacy can support users to mitigate various risks” says Winstone. “We really need to be equipping young people with the tools they need to use social media safely and positively.”

Schools, parents, and caregivers can encourage media literacy by educating youth on the many ways algorithms are shaping experiences online, how social media platforms are designed to keep people on their feed, and awareness of the risks from media usage to child self-image and identity, online relationships, online reputation, cyberbullying, managing online information, fake news, privacy, security, and copyright, says Winstone.

Appeal to teens’ natural desire for autonomy to foster this literacy, suggests Maheux. “They value the idea that they are able to make decisions with an autonomous worldview. The idea that social media companies are trying to exploit them is something that I think they want to know, and that likely bothers them,” she says.

Retrain Algorithms To Curate A Healthy Timeline

Part of today’s online self-care, especially for those suffering from anxiety or depression, is exerting some control over what content the feeds deliver by developing skills to navigate algorithms, says Winstone. Young people should understand that engaging with certain content, such as dieting or melancholy, can quickly lead to more extreme content being suggested to users, including eating disorder or self-harm related content.

“Harness and manipulate the algorithms to work in a more positive way, rather than just as a profit-making tool for the companies,” says Winstone. This can take the form of doing several searches for entertaining, funny and/or positive content – the more you engage with that content, the more the algorithm will deliver. “You can curate your experience and be proactive. Be deliberate about what you’re going on an app for, and how you can take care of yourself as you navigate it,” says Harrison.

Find Online Resources To Help Kids Thrive

“Digital media can provide opportunities for well-being and for thriving,” notes Maheux. Especially for minority youth, there’s a lot of emerging evidence about the potential benefits of engaging in digital spaces. “Digital media offers these amazing opportunities to belong to a community, to experience connection with others, to be a part of something that’s greater than oneself and have a sense of purpose that’s really valuable for adolescents,” she says. “These resources can moderate these links between general and minority stressors and mental health.”

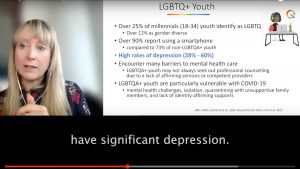

For teens who are developmentally learning about what is “normal” for dating and romantic relationships, finding those with shared lived experiences and identities can promote well-being. Maheux notes that especially for queer teens, “access to healthy and respectful dating partners can also be a huge benefit of digital media.”

Focus On Safety And Privacy On Social Platforms

It’s difficult to stay on top of all the popular platforms and features, but it’s “absolutely important” for any adult interacting with youth regularly to be familiar with the individual platform safety and privacy features such as age restrictions and media balance features, as well as good citizenship rules and practices, says Whitlock, as they can vary quite a bit. Media balance settings like “Your Activity” in Instagram allow users to track and set time limits on platform use as well as set reminders to take breaks.

Platforms such as Snapchat for example, where visual images are sent and “disappear” quickly, may give youth a false sense of security, as anyone can take a screenshot and keep the images on a more permanent basis, says Whitlock. “Being aware of where young people might get tripped up because of what the affordances are in the platform is an important part of being a supportive and a contributing adult.”

TikTok is more public, and therefore easier to protect privacy by monitoring what is being accidentally or intentionally disclosed, whereas Instagram’s features make it easier to disclose private information and harder for parents to see that disclosure, says Whitlock.

Help Youth Learn To Trust Their Gut

Equipping youth struggling with anxiety or depression to recognize when their digital media use is affecting them negatively is essential, explains Whitlock. “They need to understand what they start to feel like when the scrolling has gone from being connective or uplifting to sucking away energy and time. There is typically an inner feeling that they can learn to identify. But if they don’t know that it’s there, then they often just pass right over it and then start to spiral,” she says. Learning how to disengage can be very difficult, particularly for younger adolescents.

Help them learn how to discern the feeling they get when they are using media in ways that negatively affect them such as:

-

- Using media for avoidance

- Engaging in negatively comparing oneself to others on social media

- Feeling FOMO

Promote Healthy Sleep

Teens with anxiety tend to get more anxious on nights they have problems sleeping, says Willis. This may lead to scrolling on their phone, and engagement with social media and other online platforms that make it even more difficult to sleep. “Making sure that sleep is happening and protected is probably the most important thing that we can do,” says Whitlock.

Fritsch advocates for a media-free bedroom. “I say the bed should never be used for anything other than sleep,” she says. “You should not have a laptop in your lap. You should not be on the phone when you’re in bed because the message to your brain is that the bed is for all this stuff” instead of sleep.

However, taking devices completely out of a bedroom from a teen used to them may create more anxiety and aggravation, says Willis. One intervention he has found helpful in clinical practice is to give access to soothing digital media like an audiobook on a speaker, that may help them soothe to sleep but help them avoid being on social media.

Unique Considerations For Marginalized Youth

Youth from minority status groups experience “external” minority stressors, says Maheux, like discrimination and harassment, but also might experience something called “internalized minority stressors,” such as internalized negative attitudes towards one social group like internalized homonegativity or homophobia. “All of these stressors can collectively contribute to negative mental health outcomes like depression, suicidality, anxiety, and disordered eating.”

The online environment can actually make experiences like victimization or discrimination worse than in offline environments, says Maheux. Factors that make online victimization potentially more harmful to marginalized youth mental health are:

-

- Publicness – discriminatory experiences may have more perpetrators at once and a wider audience, creating more stress.

- 24/7 availability – difficult to escape the experience, making it feel or actually be ever-present.

- Anonymity/Disinhibition effect – people saying things online they wouldn’t say in person, making the experience harsher and more extreme to the victim.

Considering both risk and resilience factors for marginalized youth is essential to support their mental health and ability to thrive amongst the risk of hate speech, direct and vicarious discrimination and potential exploitation, says Maheux. Key resilience factors are connection, having community role models, and access to information.

Specific Online Risks For Youth Of Color Mental Health

Black and Hispanic teens are actually more likely to say they’re online constantly as compared to white teens, notes Willis. More time online means more exposure for one of the major risk factors for anxiety for youth of color – online racism. Studies have started to show that youth of color are exposed to more online racial discrimination than adults, he says, with one study showing youth experiencing over five racist encounters online in a single day.

“In addition to online racist content such as racist tweets or videos, Black and Hispanic youth have also had to more recently navigate exposure to what we call traumatic race-related events in online spaces,” he explains. Exposure to these racist traumatic events online are risk factors for Black youth and youth of color to increase their risk of anxiety and negative impacts to mental health. Exposure can occur not only on social media sites but video games and virtual reality spaces, individually or witnessed indirectly, and exposure to this content has increased since 2020 and the death of George Floyd that summer.

“Individual online racial discrimination refers to any content that’s directly targeted to a specific adolescent, whereas vicarious online racial discrimination refers to the racist content that adolescents might come across as they’re on Twitter, for example,” says Willis.

What does anxiety as a result of online racism exposure look like? Willis says to be aware of:

-

- Increased worry or rumination about going online or on social media due to fear of being targeted due to race

- Worry about seeing traumatic videos, especially if there’s been a recent traumatic occurrence in the media

- Panic symptoms when directly attacked online because of race

- Panic symptoms in response to exposure to racist content online

- Difficulty concentrating in school

- Increased worry about encountering racism offline

- Excessive avoidance of online spaces or fear/avoidance of real-life places where they may expect to experience racism

- Fear of police encounters

- Feelings of isolation from family and friends, especially in preteens

Factors that may promote resiliency in youth of color to the negative mental health impacts of online experiences of racism can be their racial identity beliefs, says Willis, which is defined as “the significance and quality of meaning that race has in the self-concept of in particular African Americans but also youth of color,” he says. “We know that racial identity is protective in that it can help you have a better sense of self-concept and also help facilitate how to cope with experiences of racism” in general, says Willis, with recent early findings also showing that these beliefs are also related to fewer anxiety symptoms even when exposed to online racism.

For parents and educators of youth of color, it’s important to be aware when these viral traumatic videos are online and to talk to children about the positive aspects of their culture and identity to help build resilience in the face of the negative messaging that they encounter, says Willis. “From research we know that using racially conscious and relevant materials in curriculum not only helps to develop positive identity beliefs, but it can actually facilitate awareness of online racism so they’re more prepared when they encounter it and are less bothered by it.”

1 Sharma, B., Lee, S. S., & Johnson, B. K. (2022). The dark at the end of the tunnel: Doomscrolling on social media newsfeeds. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 3(1: Spring 2022). https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000059

(Source: Janis Whitlock, PhD, Scientist Emerita, Cornell University; Founder and Director, Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery)

(Source: Janis Whitlock, PhD, Scientist Emerita, Cornell University; Founder and Director, Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery)